Cervelli v. Aloha Bed & Breakfast, 142 Hawai‘i 177 (2018)

415 P.3d 919

© 2019 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

1

142 Hawai‘i 177

Intermediate Court of Appeals of Hawai‘i.

Diane CERVELLI and Taeko Bufford,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

ALOHA BED & BREAKFAST, a Hawai‘i sole

proprietorship, Defendant-Appellant,

and

William D. Hoshijo, as Executive Director of the

Hawai‘i Civil Rights Commission,

Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellee.

NO. CAAP-13-0000806

|

FEBRUARY 23, 2018

Synopsis

Background: Lesbian couple, who were refused lodging

at bed and breakfast, filed a complaint for injunctive

relief, declaratory relief, and damages against bed and

breakfast, which operated as a sole proprietorship,

alleging discriminatory denial of public accommodations

in violation of state law. The Hawai‘i Civil Rights

Commission (HCRC) intervened in the case as a plaintiff.

The Circuit Court of the First Circuit, Edwin C. Nacino,

J., entered partial summary judgment for lesbian couple

and HCRC on the issues of liability and injunctive relief.

Bed and breakfast appealed.

Holdings: The Intermediate Court of Appeals, Nakamura,

C.J., held that:

bed and breakfast was “place of public accommodation”

within meaning of statute prohibiting unfair

discriminatory practices by places of public

accommodation;

the “Mrs. Murphy” exemption, providing that statutory

prohibitions against discrimination in real estate

transactions do not apply to rental of up to four rooms, did

not authorize bed and breakfast’s discriminatory conduct;

application of public accommodation statute to bed and

breakfast owner did not violate owner’s right to privacy;

application of public accommodation statute to bed and

breakfast did not violate bed and breakfast owner’s

constitutionally protected right to intimate association;

and

application of public accommodation statute to bed and

breakfast did not violate bed and breakfast owner’s free

exercise of religion.

Affirmed.

**922 APPEAL FROM THE CIRCUIT COURT OF

THE FIRST CIRCUIT (CIVIL NO. 11-1-3103)

Attorneys and Law Firms

On the briefs:

Shawn A. Luiz, James Hochberg, Honolulu, for

Defendant-Appellant

Joseph P. Infranco, Joseph E. La Rue, (Alliance

Defending Freedom), for Defendant Appellant

Jay S. Handlin, Linsay N. McAneeley, Honolulu,

(Carlsmith Ball LLP), Peter C. Renn, (Lambda Legal

Defense and Education Fund, Inc.), For

Plaintiffs-Appellees

Robin Wurtzel, Honolulu, Shirley Naomi Garcia, April L.

Wilson-South, Honolulu, (Hawai‘i Civil Rights

Commission), for Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellee

NAKAMURA, CHIEF JUDGE, and FUJISE and

REIFURTH, JJ.

Opinion

OPINION OF THE COURT BY NAKAMURA, C.J.

**923 *181 Defendant-Appellant Aloha Bed & Breakfast

(Aloha B&B) is owned and operated by Phyllis Young

(Young) as a sole proprietorship. Aloha B&B provides

lodging to transient guests, averaging between one

hundred and two hundred customers per year.

Plaintiffs-Appellees Diane Cervelli (Cervelli) and Taeko

Bufford (Bufford) (collectively, Plaintiffs), lesbian

women in a committed relationship, planned a trip to

Hawai‘i and sought lodging with Aloha B&B. Aloha

B&B and Young refused to accommodate Plaintiffs’

request for lodging based solely on their sexual

orientation.

Plaintiffs filed a Complaint in the Circuit Court of the

Cervelli v. Aloha Bed & Breakfast, 142 Hawai‘i 177 (2018)

415 P.3d 919

© 2019 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

2

First Circuit (Circuit Court)

1

against Aloha B&B, alleging

discriminatory denial of public accommodations in

violation of Hawaii Revised Statutes (HRS) Chapter 489.

2

The Hawai‘i Civil Rights Commission (HCRC)

intervened in the case as a plaintiff, after it had

determined that there was reasonable cause to believe that

unlawful discriminatory practices had occurred.

Plaintiffs and the HCRC filed a partial motion for

summary judgment on the issues of liability and

injunctive relief, and Aloha B&B filed a competing

cross-motion for summary judgment. The Circuit Court

granted Plaintiffs and the HCRC’s motion and denied

Aloha B&B’s motion. The Circuit Court ruled that Aloha

B&B violated HRS § 489-3 by discriminating against the

Plaintiffs on the basis of their sexual orientation. The

Circuit Court also enjoined Aloha B&B from “engaging

in any practices that operate to discriminate against

same-sex couples as customers.”

On appeal, Aloha B&B argues that the Circuit Court erred

in ruling that it is liable for discriminatory practices under

HRS Chapter 489. Aloha B&B maintains that because

Aloha B&B operates its business out of Young’s

residence, the Circuit Court should have applied an

exemption from prohibited discriminatory practices in

real property transactions set forth in HRS Chapter 515

for the rental of rooms by a resident. Alternatively, Aloha

B&B argues that the application of HRS Chapter 489 to

prohibit discriminatory practices under the circumstances

of this case would violate Young’s constitutional rights.

Based on these arguments, Aloha B&B contends that the

Circuit Court erred in granting Plaintiffs and the HCRC’s

motion for partial summary judgment and in denying

Aloha B&B’s motion for summary judgment. We affirm.

BACKGROUND

I.

Aloha B&B operates out of a four bedroom home in the

Mariner’s Ridge section of Hawai‘i Kai, where Young

and her husband reside. Young operates Aloha B&B as a

sole proprietorship and offers three rooms in her residence

to guests for overnight lodging. Rooms at Aloha B&B are

offered at a nightly rate of $80 to $100, and there is a

three-night minimum booking requirement. In addition to

the nightly rate, Aloha B&B charges and collects general

excise taxes from its customers as well as transient

accommodation taxes, which only providers of transient

accommodations are required to pay. Aloha B&B remits

these taxes to the State of Hawai‘i.

Aloha B&B does not offer rooms to customers for use as

a permanent residence, and Young never describes herself

as a landlord to her guests. Aloha B&B averages one

hundred to two hundred customers per year. The median

length of stay for Aloha B&B customers is four to five

days. The majority of customers stay for less than a week,

about 95 percent or more stay for less than two weeks,

and more than 99 percent stay for less than a month. In

addition to overnight lodging, customers at Aloha B&B

are provided breakfast, pool access, wireless internet

access, and other amenities. Almost all of **924 *182

Aloha B&B customers, an estimated 99 percent, are

travelers who do not live in Hawai‘i.

Aloha B&B advertises its services to the general public

through its own website as well as through multiple

third-party websites. Aloha B&B’s website, freely

accessible through the internet, provides a phone number

and email address for potential customers to contact

Aloha B&B, and it contains graphics stating “Best Choice

Hawaii Hotel” and “Best Choice Oahu Hotels.” Aloha

B&B also advertises through various

bed-and-breakfast-related websites to generate more

business for itself, including paying an annual fee of

between $400 to $500 to BedandBreakfast.com.

II.

Plaintiffs Cervelli and Bufford, two lesbian women in a

committed relationship, began planning a trip to Hawai‘i

to visit a friend. Plaintiffs, who resided in California,

wanted to stay near their friend, who lived in Hawai‘i Kai.

Cervelli emailed Aloha B&B to inquire if a room was

available for their planned trip. Young responded by

email the same day, stating that a room was available for

six days and providing instructions on how to complete

the reservation.

Two weeks later, Cervelli called Aloha B&B to book the

reservation and spoke with Young, who indicated that the

room was still available. While Young was writing up the

reservation, Cervelli mentioned that she would be

accompanied by another woman named “Taeko.” Young

stopped and asked whether Cervelli and her companion

Cervelli v. Aloha Bed & Breakfast, 142 Hawai‘i 177 (2018)

415 P.3d 919

© 2019 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

3

were lesbians. When Cervelli said “yes,” Young

responded, “[W]e’re strong Christians. I’m very

uncomfortable in accepting the reservation from you.”

Young refused to accept the reservation from Cervelli and

terminated the phone call by hanging up.

Cervelli called Bufford in tears and explained what had

happened. Bufford then called Young and attempted to

reserve a room, but Young again refused to accept the

reservation. Bufford ‘asked Young if her refusal was

because Bufford and Cervelli were lesbians, to which

Young responded “yes.” Bufford had two phone

conversations with Young that day. Young referred to her

religious beliefs in discussing her refusal to provide a

room to Plaintiffs. Apart from Plaintiffs’ sexual

orientation, there was no other reason for Young’s refusal

to accept Plaintiffs’ request for a room.

III.

Cervelli and Bufford each filed a complaint against Aloha

B&B with the HCRC alleging discrimination in public

accommodations on the basis of sexual orientation.

Young was interviewed during the HCRC’s investigation

and was asked to describe the religious beliefs that she

claimed precluded her from accepting Cervelli and

Bufford’s reservation. Young stated that she is Catholic;

that she believes that homosexuality is wrong; that she

believes that sexual relations between same-sex couples

(regardless of whether they are legally married) are

immoral; and that she therefore refused to provide

Cervelli and Bufford with a room. The HCRC found that

there was reasonable cause to believe that Aloha B&B

had committed an unlawful discriminatory practice

against Cervelli and Bufford in violation of HRS § 489-3.

The HCRC subsequently closed its cases based on

Cervelli’s and Bufford’s election to pursue a court action,

and it issued “right to sue” notices to Cervelli and

Bufford.

IV.

Plaintiffs subsequently filed in the Circuit Court a

Complaint for injunctive relief, declaratory relief, and

damages against Aloha B&B, alleging discrimination on

the basis of sexual orientation in violation of HRS

Chapter 489. The HCRC filed a motion to intervene in the

case as a plaintiff because it found the case was one of

“general importance” given the HCRC’s mission to

eliminate discrimination. The Circuit Court granted the

HCRC’s motion to intervene as a plaintiff.

Plaintiffs and the HCRC filed a motion for partial

summary judgment with respect to liability and injunctive

relief.

3

Aloha B&B filed a cross-motion for summary

judgment.

**925 *183 The Circuit Court held a hearing on the

parties’ competing motions for summary judgment. At the

hearing, counsel for Aloha B&B acknowledged that

“discrimination is a horrible evil” and that “in places of

public accommodation discrimination is a horrible evil.”

Aloha B&B’s counsel also acknowledged that Aloha

B&B admits that it “does provide lodging to transient

guests.”

4

However, Aloha B&B’s counsel argued that the

law prohibiting discrimination in public accommodations,

HRS Chapter 489, does not apply to Aloha B&B because

it uses Young’s residence to provide lodging to transient

guests. Aloha B&B’s counsel argued that Aloha B&B’s

use of a residence means that it is not a “place of public

accommodation” subject to the requirements of Chapter

489, but instead is governed by HRS Chapter 515.

The Circuit Court granted Plaintiffs and the HCRC’s

motion for partial summary judgment with respect to

liability and declaratory and injunctive relief, and it

denied Aloha B&B’s cross-motion for summary judgment

as moot. In its Summary Judgment Order,

5

the Circuit

Court found that:

[Aloha B&B] is governed by Chapter 489, HRS, not

Chapter 515, HRS, and [Aloha B&B] constitutes a

place of public accommodation under HRS § 489-2,

because its goods, services, facilities, privileges,

advantages, or accommodations are extended, offered,

sold, or otherwise made available to the general public

as customers, clients, or visitors. [Aloha B&B] also

constitutes “[a]n inn, hotel, motel, or other

establishment that provides lodging to transient guests”

and “[a] facility providing services relating to travel or

transportation.” HRS § 489-2. [Aloha B&B] violated

HRS § 489-3 by discriminating against Plaintiffs Diane

Cervelli and Taeko Bufford on the basis of their sexual

orientation as lesbians.

(Certain brackets in original.) The Circuit Court enjoined

and prohibited “Defendant Aloha Bed & Breakfast, a

Hawai‘i sole proprietorship of Phyllis Young,” and its

officers, agents, and employees “from engaging in any

practices that operate to discriminate against same-sex

couples as customers of Aloha Bed & Breakfast[.]”

Cervelli v. Aloha Bed & Breakfast, 142 Hawai‘i 177 (2018)

415 P.3d 919

© 2019 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

4

The Circuit Court entered its Summary Judgment Order

on April 15, 2013. The parties subsequently submitted a

stipulated application to file an interlocutory appeal from

the Summary Judgment Order, which the Circuit Court

granted.

DISCUSSION

I.

Aloha B&B argues that the Circuit Court erred in ruling

that it is liable for discriminatory practices under HRS

Chapter 489. Aloha B&B argues that it is not subject to

HRS Chapter 489, but that its activities are governed by

HRS Chapter 515. In particular, Aloha B&B asserts that

an exemption from prohibited discriminatory practices in

real property transactions set forth in HRS § 515-4(a)(2)

protects it from liability in this case.

Plaintiffs and the HCRC, on the other hand, argue that

Aloha B&B is clearly a place of public accommodation

that is subject to HRS Chapter 489. Plaintiffs and the

HCRC argue that Aloha B&B cannot “borrow” an

exemption applicable to a different law (HRS Chapter

515) to avoid liability for violating the public

accommodations law (HRS Chapter 489) on which

Plaintiffs seek relief. They also argue that the HRS

Chapter 515 exemption relied upon by Aloha B&B only

applies to long-term living arrangements in which tenants

are seeking permanent housing, and not to the short-term

transient lodging provided by Aloha B&B to its

customers.

As explained below, we conclude that the Circuit Court

properly granted partial summary judgment in favor of

Plaintiffs and the HCRC.

**926 *184 A.

The statutory provisions relevant to this appeal are as

follows.

Plaintiffs’ Complaint against Aloha B&B alleged

discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in public

accommodations, in violation of HRS Chapter 489. HRS

§ 489-3 provides:

Unfair discriminatory practices that

deny, or attempt to deny, a person

the full and equal enjoyment of the

goods, services, facilities,

privileges, advantages, and

accommodations of a place of

public accommodation on the basis

of race, sex, including gender

identity or expression, sexual

orientation, color, religion,

ancestry, or disability are

prohibited.

HRS § 489-2 (2008) defines the terms “place of public

accommodation” and “sexual orientation” for purposes of

HRS Chapter 489, in relevant part, as follows:

“Place of public accommodation” means a business,

accommodation, refreshment, entertainment,

recreation, or transportation facility of any kind whose

goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages, or

accommodations are extended, offered, sold, or

otherwise made available to the general public as

customers, clients, or visitors. By way of example, but

not of limitation, place of public accommodation

includes facilities of the following types:

(1) A facility providing services relating to travel

or transportation; [or]

(2) An inn, hotel, motel, or other establishment

that provides lodging to transient guests;

....

“Sexual orientation” means having a preference for

heterosexuality, homosexuality, or bisexuality, having a

history of any one or more of these preferences, or

being identified with any one or more of these

preferences.

Aloha B&B argues that its activities are governed by HRS

Chapter 515 and that it falls within the exemption from

prohibited discriminatory practices set forth in HRS §

515-4(a)(2). HRS § 515-3 (2006), provides in relevant

part:

Cervelli v. Aloha Bed & Breakfast, 142 Hawai‘i 177 (2018)

415 P.3d 919

© 2019 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

5

It is a discriminatory practice for an owner or any other

person engaging in a real estate transaction, or for a

real estate broker or salesperson, because of race, sex,

including gender identity or expression, sexual

orientation, color, religion, marital status, familial

status, ancestry, disability, age, or human

immunodeficiency virus infection:

(1) To refuse to engage in a real estate transaction

with a person;

....

[6]

HRS § 515-4(a)(2) (Supp. 2011) provides:

(a) Section 515-3 does not apply:

...

(2) To the rental of a room or up to four rooms in a

housing accommodation by an owner or lessor if the

owner or lessor resides in the housing

accommodation.

[7]

HRS § 515-2 (2006) defines the terms “housing

accommodation,” “real estate transaction” and “real

property” for purposes of HRS Chapter 515, in relevant

part, as follows:

“Housing accommodation” includes any improved or

unimproved real property, or part thereof, which is used

or occupied, or is intended, arranged, or designed to be

used or occupied, as the home or residence of one or

more individuals.

....

“Real estate transaction” includes the sale, exchange,

rental, or lease of real property.

**927 *185 “Real property” includes buildings,

structures, real estate, lands, tenements, leaseholds,

interests in real estate cooperatives, condominiums, and

hereditaments, corporeal and incorporeal, or any

interest therein.

The definition of “sexual orientation” in HRS § 515-2 is

identical to the definition in HRS § 489-2.

B.

In rendering its decision, the Circuit Court construed

provisions of HRS Chapter 489 and HRS Chapter 515.

Statutory construction is a question of law, which we

review de novo under the right/wrong standard. Lingle v.

Hawai‘i Gov’t Empls. Ass’n. AFSCME, Local 152,

AFL-CIO, 107 Hawai‘i 178, 183, 111 P.3d 587, 592

(2005). In interpreting a statute, we are guided by the

following well-established principles:

When construing a statute, our foremost obligation is to

ascertain and give effect to the intention of the

legislature, which is to be obtained primarily from the

language contained in the statute itself. And we must

read statutory language in the context of the entire

statute and construe it in a manner consistent with its

purpose.

When there is doubt, doubleness of meaning, or

indistinctiveness or uncertainty of an expression used

in a statute, an ambiguity exists.

In construing an ambiguous statute, the meaning of the

ambiguous words may be sought by examining the

context with which the ambiguous words, phrases, and

sentences may be compared, in order to ascertain their

true meaning. Moreover, the courts may resort to

extrinsic aids in determining legislative intent. One

avenue is the use of legislative history as an

interpretive tool.

This court may also consider the reason and spirit of

the law, and the cause which induced the legislature to

enact it to discover its true meaning. Laws in pari

materia, or upon the same subject matter, shall be

construed with reference to each other. What is clear in

one statute may be called upon in aid to explain what is

doubtful in another.

Haole v. State, 111 Hawai‘i 144, 149-50, 140 P.3d 377,

382-83 (2006) (block quote format altered; citation and

brackets omitted).

C.

Having identified the statutory provisions at issue and the

established principles for statutory interpretation, we

proceed to consider the parties’ statutory interpretation

claims. We conclude that the Circuit Court properly ruled

that there are no material facts in dispute and that Aloha

B&B violated HRS § 489-3 by discriminating against

Plaintiffs on the basis of their sexual orientation.

Cervelli v. Aloha Bed & Breakfast, 142 Hawai‘i 177 (2018)

415 P.3d 919

© 2019 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

6

HRS § 489-3 prohibits “[u]nfair discriminatory practices

that deny, or attempt to deny, a person the full and equal

enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, privileges,

advantages, and accommodations of a place of public

accommodation on the basis of ... sexual orientation ....”

Aloha B&B admitted that the sole reason it refused to

provide lodging to Plaintiffs was because of their sexual

orientation. Young testified in her deposition that there

was no other reason for Aloha B&B’s refusal.

It is also clear based on the plain statutory language that

Aloha B&B is a “place of public accommodation.” That

term is defined by HRS § 489-2 to mean “a business,

accommodation, ... recreation, or transportation facility of

any kind whose goods, services, facilities, ... or

accommodations are extended, offered, sold, or otherwise

made available to the general public as customers, clients,

or visitors.” Aloha B&B admitted in its responsive

pretrial statement that “it offers bed and breakfast services

to the general public.” The evidence presented by

Plaintiffs and the HCRC supports this admission. The

evidence showed that Aloha B&B advertises and offers its

services to the general public through its own website as

well as through multiple third-party websites that are

freely accessible over the internet; it makes its services

available to a large number of customers, an average of

between one hundred and two hundred per year; and aside

from same-sex couples and smokers, it generally accepts

anyone as a customer as long as the person is willing to

pay and a room is available.

**928 *186 More importantly, the statutory definition of

“place of public accommodation” specifically includes,

“[b]y way of example, but not of limitation,” “[a]n inn,

hotel, motel, or other establishment that provides lodging

to transient guests[.]” HRS § 489-2 (emphasis added).

Aloha B&B admitted that it “does provide lodging to

transient guests.” The undisputed evidence showed that

Aloha B&B customers only stay for short periods of time

- - the majority for less than a week and about 95 percent

for less than two weeks. Aloha B&B does not offer rooms

to customers for permanent housing or for use as a

residence, and Young does not view herself as the

landlord of the guests. In addition, Aloha B&B collects

from its customers, and pays to the State, a transient

accommodation tax, which only providers of transient

accommodations are required to pay.

Based on Aloha B&B’s own admissions as well as the

undisputed evidence, we conclude that Aloha B&B falls

squarely within the statutory definition of “place of public

accommodation” as an “establishment that provides

lodging to transient guests[.]” Our conclusion is bolstered

by the stated purpose of HRS Chapter 489 and the

Legislature’s directive on how it should be construed.

HRS § 489-1(a) (2006) states that the purpose of HRS

Chapter 489 “is to protect the interests, rights, and

privileges of all persons within the State with regard to

access and use of public accommodations by prohibiting

unfair discrimination.” HRS § 489-1(b) (2006) then

directs that HRS Chapter 489 “shall be liberally construed

to further” these purposes.

When the plain language of the statutory definition of

“place of public accommodation” is liberally construed to

further the anti-discrimination purposes of HRS Chapter

489, it reinforces our firm conclusion that Aloha B&B is a

place of public accommodation. We conclude that the

Circuit Court correctly ruled that Aloha B&B constitutes

a place of public accommodation that is subject to HRS

Chapter 489. It is undisputed that Aloha B&B refused to

provide Plaintiffs with lodging on the basis of their sexual

orientation. Therefore, we affirm the Circuit Court’s

determination that Aloha B&B violated HRS § 489-3 by

discriminating against Plaintiffs on the basis of their

sexual orientation.

8

D.

In arguing that its actions were not prohibited by HRS

489-3, Aloha B&B relies on an exemption applicable to a

different law, HRS Chapter 515, a law which generally

prohibits discrimination in real property transactions. In

particular, Aloha B&B relies on the exemption set forth in

HRS § 515-4(a)(2), a so-called “Mrs. Murphy”

exemption.

9

HRS § 515-4(a)(2) provides that the

prohibitions in HRS § 515-3 against discrimination in real

estate transactions do not apply “[t]o the rental of ... up to

four rooms in a housing accommodation by an owner or

lessor if the owner or lessor resides in the housing

accommodation.” Aloha B&B argues that the HRS §

515-4(a)(2) exemption supersedes the prohibition against

discrimination set forth in HRS § 489-3 and therefore

authorized its discriminatory conduct in this case. We

disagree.

1.

In analyzing Aloha B&B’s argument, we begin by

Cervelli v. Aloha Bed & Breakfast, 142 Hawai‘i 177 (2018)

415 P.3d 919

© 2019 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

7

focusing on our “foremost obligation ... to ascertain and

give effect” to the Legislature’s intent in enacting the

statutory provisions. As noted, through HRS § 489-1, the

Legislature mandated that HRS Chapter 489 shall be

liberally construed to further its purposes of protecting

people’s rights to access and to use public

accommodations by prohibiting unfair discrimination.

HRS Chapter 515 is also directed at prohibiting

discrimination and “shall be construed according to the

fair import of its terms and shall be liberally construed.”

HRS § 515-1 (2006).

**929 *187 By providing remedies for discrimination and

the injuries caused by discrimination, HRS Chapter 489

and HRS Chapter 515 are remedial statutes.

10

“Remedial

statutes are liberally construed to suppress the perceived

evil and advance the enacted remedy.” Flores v. United

Air Lines, Inc., 70 Haw. 1, 12, 757 P.2d 641, 647 (1988)

(internal quotation marks, citation, and brackets omitted).

In addition, “exceptions to a remedial statute should be

narrowly construed[.]” EEOC v. Borden’s, Inc., 551

F.Supp. 1095, 1110 (D. Ariz. 1982); see State v. Russell,

62 Haw. 474, 479-80, 617 P.2d 84, 88 (1980) (“The

importation of exceptions into statutes properly affected

with a public interest is not lightly to be made. ... It is a

well settled rule of statutory construction that exceptions

to legislative enactments must be strictly construed.”);

United States v. Columbus Country Club. 915 F.2d 877,

883 (1990) (construing exemptions to federal Fair

Housing Act narrowly). Accordingly, we liberally

construe the scope of the protection against discrimination

provided by HRS Chapter 489, and we narrowly or

strictly construe the scope of the exemption from

prohibited discrimination provided by HRS § 515-4(a)(2).

The Hawai‘i Legislature’s actions in omitting a “Mrs.

Murphy” exemption when it enacted HRS Chapter 489

indicates its intent that no such exemption would apply to

discrimination in public accommodations and the type of

conduct engaged in by Aloha B&B in this case. The “Mrs.

Murphy” exemption in HRS Chapter 515 was enacted in

1967. See 1967 Haw. Sess. Laws Act 193, § 4 at 196.

Almost twenty years later, the Hawai‘i Legislature

enacted HRS Chapter 489, which was patterned after the

public accommodation provisions of the federal 1964

Civil Rights Act. See State v. Hoshijo ex rel. White, 102

Hawai‘i 307, 317-18, 76 P.3d 550, 560 (2003). The

federal public accommodation provisions contain the

“Mrs. Murphy” exemption in the provision defining a

“place of public accommodation” to include an

“establishment which provides lodging to transient

guests[.]” See 42 U.S.C. § 2000a(b)(1). Although the

corresponding Hawai‘i provision adopts portions of the

federal provision word for word, the “Mrs. Murphy”

exemption is conspicuously omitted from the Hawaii

provision.

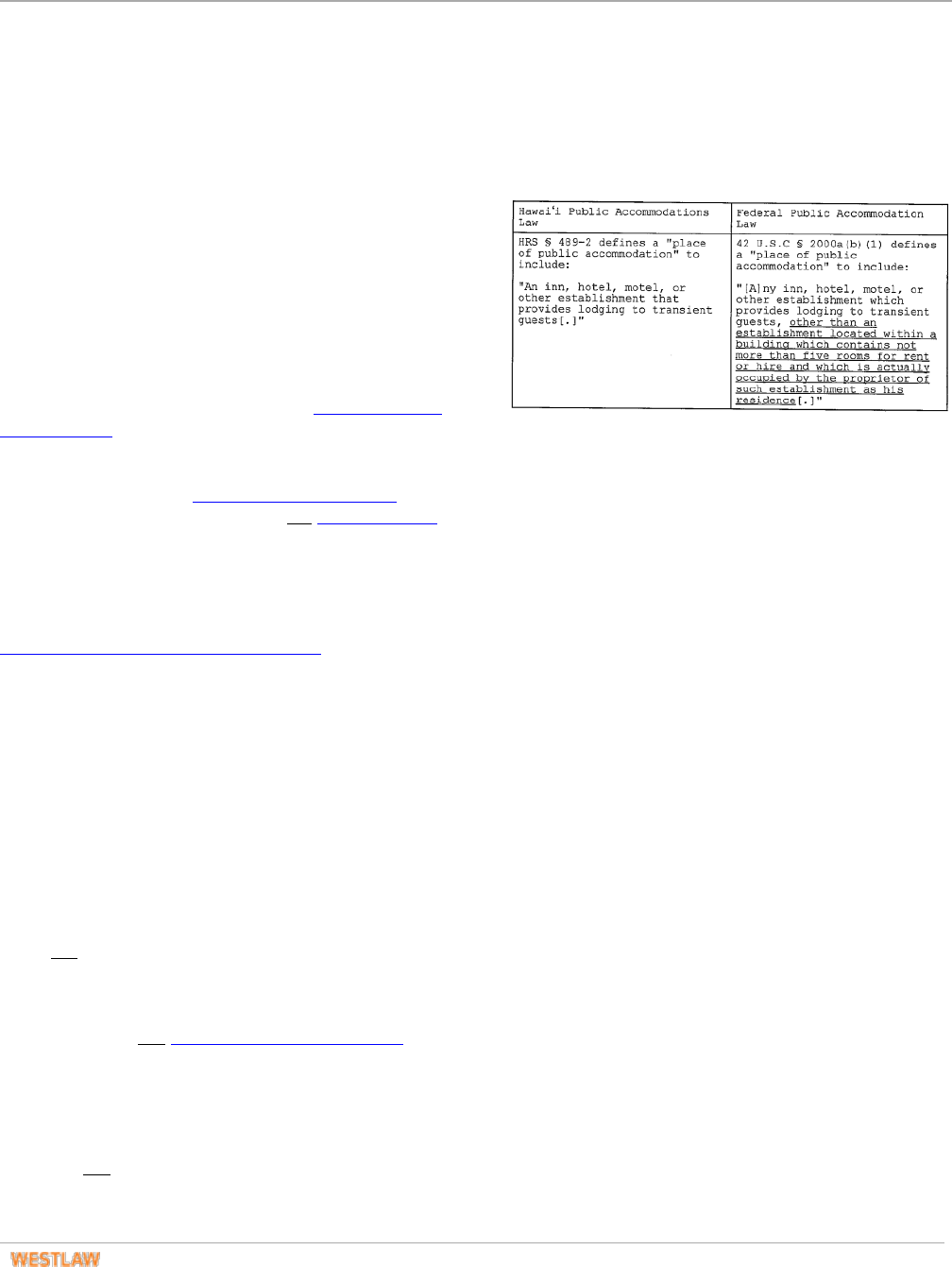

A side by side comparison of the two provisions is as

follows:

We conclude that the Hawaii Legislature’s omission of

the “Mrs. Murphy” exemption in enacting HRS Chapter

489 provides persuasive evidence that it did not intend

such an exemption to apply to establishments, like Aloha

B&B, that provide lodging to transient guests. We also

conclude that Congress’ inclusion of the “Mrs. Murphy”

exemption is instructive, for it demonstrates that Congress

believed that a person’s residence may **930 *188

constitute a “place of public accommodation” as an

“establishment which provides lodging to transient

guests.” If a person’s residence could not constitute a

place of public accommodation, then the “Mrs. Murphy”

exemption would not be necessary in the federal public

accommodation provision. Congress’ inclusion of the

“Mrs. Murphy” exemption in the federal public

accommodation law supports our conclusion that a place

of public accommodation includes a bed and breakfast

business, like Aloha B&B, that uses the proprietor’s

residence to provide lodging to transient guests.

2.

Contrary to Aloha B&B, we do not view HRS Chapter

489 and HRS § 515-4(a)(2) to be in irreconcilable

conflict. In this regard, we note that the term “rental” as

used in HRS § 515-4(a)(2) is not specifically defined.

Also, because HRS § 515-4(a)(2) is an exception to a

remedial statute, we construe it narrowly. We conclude

that it is possible to reconcile HRS Chapter 489 and HRS

§ 515-4(a)(2) by construing the phrase “rental of a room”

for purposes of HRS § 515-4(a)(2) to exclude short-term

lodging provided to transient guests covered by HRS

Chapter 489 and as applying only to longer-term living

Cervelli v. Aloha Bed & Breakfast, 142 Hawai‘i 177 (2018)

415 P.3d 919

© 2019 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

8

arrangements where more permanent housing is sought.

Such a construction would be consistent with the manner

in which the Legislature has characterized the “Mrs.

Murphy” exemption set forth in HRS § 515-4 (a)(2).

In enacting the HRS § 515-4(a)(2) exemption in 1967, the

Legislature referred to it as the “tight living” exemption.

See H. Stand. Comm. Rep. No. 874, in 1967 House

Journal, at 819. Furthermore, in amending HRS Chapter

515 in 2005 to add sexual orientation to the types of

discrimination precluded by HRS § 515-3, the Legislature

described the “Mrs. Murphy” exemption set forth in HRS

515-4(a)(2) as follows: “Housing laws presently permit

landlords to follow their individual value systems in

selecting tenants to live in the landlords’ own homes[.]”

2005 Haw. Sess. Laws Act 214, § 1 at 688 (emphasis

added). This characterization of the “Mrs. Murphy”

exemption indicates that the Legislature understood the

exemption to apply to longer-term living or housing

arrangements - - where a landlord-tenant relationship

would be established. See State v. Sullivan, 97 Hawai‘i

259, 266, 36 P.3d 803, 810 (2001) (“ ‘[S]ubsequent

legislative history or amendments’ may be examined in

order to confirm our interpretation of statutory

provisions.” (citation omitted)).

Here, Aloha B&B admitted that it provides lodging to

transient guests and that no landlord-tenant relationship is

established during the guests’ short-term stays.

Construing the phrase “rental of a room” for purposes of

HRS § 515-4(a)(2) to exclude short-term lodging

provided to transient guests and as applying only to

longer-term living arrangements would serve the

Legislature’s purposes for enacting both HRS Chapter

489 and HRS § 515-4(a)(2). It would advance the

Legislature’s goal of prohibiting discrimination in public

accommodations, while permitting landlords “to follow

their individual value systems” in selecting a tenant who

will reside with them on a longer-term basis in their own

homes. This construction would also avoid any

irreconcilable conflict between HRS Chapter 489 and

HRS § 515-4(a)(2). See State v. Vallesteros, 84 Hawai‘i

295, 303, 933 P.2d 632, 640 (1997) (“[W]here the statutes

simply overlap in their application, effect will be given to

both if possible, as repeal by implication is disfavored.”

(block quote format and citation omitted)).

3.

But even if there were an irreconcilable conflict between

HRS Chapter 489 and HRS § 515-4(a)(2), we conclude

that Chapter 489 would control as it is the more specific

statute with respect to Aloha B&B and Aloha B&B’s

actions that are at issue in this case. See id. (“[W]here

there is a ‘plainly irreconcilable’ conflict between a

general and a specific statute concerning the same subject

matter, the specific will be favored.” (block quote format

and citation omitted)). The plain language of HRS

Chapter 489 specifically applies to and governs an

“establishment that provides lodging to transient guests.”

See HRS § 489-2. This language perfectly describes

Aloha B&B. HRS Chapter 489 also directly addresses the

precise conduct at issue in this case - - the discriminatory

refusal by a public accommodation **931 *189

establishment to provide lodging to transient guests based

on their sexual orientation. See HRS § 489-3. HRS §

515-4(a)(2), on the other hand, applies more generally to

the “rental of rooms,” without specifying the time period

involved or whether the provision of lodging to transient

guests is covered. We conclude that HRS Chapter 489 is

the more specific statute regarding the subject matter of

this case.

11

II.

We now turn to address Aloha B&B’s constitutional

claims. Aloha B&B contends that the application of HRS

Chapter 489 to its conduct in this case would violate

Young’s constitutional rights to privacy, intimate

association, and free exercise of religion. We disagree.

We review “questions of constitutional law de novo,

under the right/wrong standard,” and we “answer

questions of constitutional law by exercising [our] own

independent judgment based on the facts of the case.

Malahoff v. Saito, 111 Hawai‘i 168, 181, 140 P.3d 401,

414 (2006) (citation and brackets omitted). “[E]very

enactment of the [Hawai‘i] [L]egislature is presumptively

constitutional, and a party challenging the statute has the

burden of showing [the alleged] unconstitutionality

beyond a reasonable doubt.” State v. Mueller, 66 Haw.

616, 627, 671 P.2d 1351, 1358 (1983). The alleged

constitutional violation “should be plain, clear, manifest,

and unmistakable.” Kaho‘ohanohano v. State, 114

Hawai‘i 302, 339, 162 P.3d 696, 733 (2007).

Cervelli v. Aloha Bed & Breakfast, 142 Hawai‘i 177 (2018)

415 P.3d 919

© 2019 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

9

A.

Aloha B&B argues that applying HRS Chapter 489 to

prohibit it from discriminating against Plaintiffs and

others based on their sexual orientation violates Young’s

right to privacy. We disagree.

The “evil of unequal treatment, which is the injury to an

individual’s sense of self-worth and personal integrity” is

“the chief harm resulting from the practice of

discrimination by establishments serving the general

public.” King v. Greyhound Lines, Inc., 61 Or.App. 197,

656 P.2d 349, 352 (Or. Ct. App. 1982), cited in Hoshijo

ex rel. White, 102 Hawai‘i at 317 n.22, 76 P.3d at 560

n.22. Unfair discriminatory practices in general, and such

practices in places of public accommodation in particular,

“deprive[ ] persons of their individual dignity and den[y]

society the benefits of wide participation in political,

economic, and cultural life.” Roberts v. United States

Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609, 625, 104 S.Ct. 3244, 82 L.Ed.2d

462 (1984).

Hawai‘i has a compelling state interest in prohibiting

discrimination in’ public accommodations. “[A]cts of

invidious discrimination in the distribution of publicly

available goods, services, and other advantages cause

unique evils that government has a compelling interest to

prevent[.]” Id. at 628, 104 S.Ct. 3244. A State’s interest in

assuring equal access is not “limited to the provision of

purely tangible goods and services,” and a State has broad

authority to create rights of public access. Id. at 625, 104

S.Ct. 3244.

Aloha B&B argues that the right to privacy is “the right to

be left alone.” However, to **932 *190 the extent that

Young has chosen to operate her bed and breakfast

business from her home, she has voluntarily given up the

right to be left alone. In choosing to operate Aloha B&B

from her home, Young, for commercial purposes, has

opened up her home to over one hundred customers per

year, charging them money for access to her home.

Indeed, the success of Aloha B&B’s business and its

profits depend on members of the general public entering

Young’s home as customers. In other words, the success

of Aloha B&B’s business requires that Young not be left

alone.

Aloha B&B also argues that the right to privacy has

special force in a person’s own home. However, given

Young’s choice to use her home for business purposes as

a place of public accommodation, it is no longer a purely

private home. “The more an owner, for [her] advantage,

opens [her] property for use by the public in general, the

more do [her] rights become circumscribed by the

statutory and constitutional rights of those who use it.”

State v. Viglielmo, 105 Hawai‘i 197, 206, 95 P.3d 952,

961 (2004) (internal quotation marks and citation

omitted). In addition, the State retains the right to regulate

activities occurring in a home where others are harmed or

likely to be harmed. See State v. Kam, 69 Haw. 483, 492,

748 P.2d 372, 378 (1988); Mueller, 66 Haw. at 618-19,

628, 671 P.2d at 1353-54, 1359 (finding no privacy right

to engage in prostitution in one’s home). Aloha B&B’s

discriminatory conduct caused direct harm to Plaintiffs

and threatens to harm other members of the general

public.

The privacy right implicated by this case is not the right

to exclude others from a purely private home, but rather

the right of a business owner using her home as a place of

public accommodation to use invidious discrimination to

choose which customers the business will serve. “The

Constitution does not guarantee a right to choose

employees, customers, suppliers, or those with whom one

engages in simple commercial transactions, without

restraint from the State.” Roberts, 468 U.S. at 634, 104

S.Ct. 3244 (O’Connor, J., concurring). We conclude that

Young’s asserted right to privacy did not entitle her to

refuse to provide Plaintiffs with lodging based on their

sexual orientation and that the application of HRS

Chapter 489 to prohibit such discriminatory conduct does

not violate her right to privacy. See Mueller, 66 Haw. at

618-19, 628, 671 P.2d at 1353-54, 1359.

B.

Aloha B&B claims that applying HRS Chapter 489 to

prohibit it from denying accommodations to Plaintiffs and

others based on their sexual orientation violates Young’s

constitutionally protected right to intimate association.

We disagree.

In recognizing the constitutional right of intimate

association, the Supreme Court “has concluded that

choices to enter into and maintain certain intimate human

relationships must be secured against undue intrusion by

the State because of the role of such relationships in

safeguarding the individual freedom that is central to our

constitutional scheme.” Roberts, 468 U.S. at 617-18, 104

S.Ct. 3244. “[C]ertain kinds of personal bonds have

played a critical role in the culture and traditions of the

Nation by cultivating and transmitting shared ideals and

beliefs[.]” Id. at 618-19, 104 S.Ct. 3244. The right of

intimate association protects family relationships and

similar highly personal relationships, which “by their

Cervelli v. Aloha Bed & Breakfast, 142 Hawai‘i 177 (2018)

415 P.3d 919

© 2019 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

10

nature, involve deep attachments and commitments to the

necessarily few other individuals with whom one shares

not only a special community of thoughts, experiences,

and beliefs but also distinctively personal aspects of one’s

life.” Id. at 619-20, 104 S.Ct. 3244. The protected

relationships “are distinguished by such attributes as

relative smallness, a high degree of selectivity in

decisions to begin and maintain the affiliation, and

seclusion from others in critical aspects of the

relationship.” Id. at 620, 104 S.Ct. 3244. Conversely, an

association lacking these qualities, “such as a large

business enterprise,” are not protected. Id.

The Supreme Court specifically referred to family

relationships to exemplify and to suggest limitations on

the kinds of relationships entitled to constitutional

protection. Id. at 619, 104 S.Ct. 3244. The factors relevant

for a court to consider in determining whether a particular

relationship is entitled **933 *191 to protection are “the

group’s size, its congeniality, its duration, the purposes

for which it was formed, and the selectivity in choosing

participants.” IDK, Inc. v. Clark County, 836 F.2d 1185,

1193 (9th Cir. 1988).

Considering these factors, we conclude that applying HRS

Chapter 489 to Aloha B&B does not violate Young’s

right to intimate association. The relationship between

Aloha B&B and the customers to whom it provides

transient lodging is not the type of intimate relationship

that is entitled to constitutional protection against a law

designed to prohibit discrimination in public

accommodations.

With respect to the group’s size, Aloha B&B provides

transient lodging to between one hundred and two

hundred customers per year. Aloha B&B has

accommodated customers in up to three rooms at a time

for twenty years. The hundreds of customer relationships

Aloha B&B forms through its business is far from the

“necessarily few” family-type relationships that are

subject to constitutional protection. See Roberts, 468 U.S.

at 620-21, 104 S.Ct. 3244 (holding that relationships

formed through membership in business groups with 400

and 430 members were not protected); IDK, 836 F.2d at

1193 (concluding that while an escort and a client “are the

smallest possible association[,]” this relationship was not

protected because, among other reasons, an escort may

have many other clients, and the relationship “lasts for a

short period and only as long as the client is willing to pay

the fee”).

With respect to the purpose for which the relationship is

formed, Aloha B&B forms relationships with its

customers for commercial, business purposes, and it is

only the commercial aspects of the relationship that HRS

Chapter 489 regulates. Young testified that the primary

purpose of Aloha B&B is to “make money.” She also

admitted that if she could not make money by running

Aloha B&B, she “wouldn’t operate it.” Young does not

operate Aloha B&B for the purpose of developing “deep

attachments and commitments” to its customers. See id. at

620, 104 S.Ct. 3244.

With respect to selectivity, duration, and congeniality,

Aloha B&B generally is not selective about whom it will

accept as customers, provides short-term, transient

lodging, and does not form lasting relationships with

customers. With narrow exceptions such as same-sex

couples and smokers, Aloha B&B basically provides

lodging to “any member of the public who is willing to

pay.” Aloha B&B does not inquire into the background of

its prospective customers, such as their political or

religious beliefs, before allowing them to book a

reservation.

12

Aloha B&B’s customers only stay for short

periods of time. The majority stay for less than a week,

about 95 percent less than two weeks, and over 99 percent

less than a month. While Young stated that “people come

as guests and leave as friends,” she acknowledged that she

had difficulty putting customers’ “faces to the name” a

month after they left.

Aloha B&B and Young’s relationship with customers

arising from the commercial operation of Aloha B&B

does not constitute an intimate, family-type relationship

that involves “deep attachments and commitments to the

necessarily few other individuals with whom one shares

not only a special community of thoughts, experiences,

and beliefs but also distinctively personal aspects of one’s

life.” Roberts, 468 U.S. at 620, 104 S.Ct. 3244. Applying

HRS Chapter 489 to prohibit the discriminatory conduct

engaged in by Aloha B&B in this case does not violate

Young’s right to intimate association.

C.

Aloha B&B contends that application of HRS Chapter

489 to its conduct in this case violates Young’s

constitutional right to free exercise of religion. We

disagree.

**934 *192 The Free Exercise Clause of the First

Amendment, which is applicable to the States through the

Fourteenth Amendment, provides that “Congress shall

make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or

Cervelli v. Aloha Bed & Breakfast, 142 Hawai‘i 177 (2018)

415 P.3d 919

© 2019 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

11

prohibiting the free exercise thereof ....” U.S. Const.,

amend. I. (emphasis added). The protections of the Free

Exercise Clause apply to laws that target religious beliefs

or religiously motivated conduct. Church of the Lukumi

Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah, 508 U.S. 520,

532-34, 113 S.Ct. 2217, 124 L.Ed.2d 472 (1993).

However, the Supreme Court has held that “the right of

free exercise does not relieve an individual of the

obligation to comply with a ‘valid and neutral law of

general applicability on the ground that the law proscribes

(or prescribes) conduct that his religion prescribes (or

proscribes).’ ” Employment Div., Dept. of Human

Resources of Ore. v. Smith, 494 U.S. 872, 879, 110 S.Ct.

1595, 108 L.Ed.2d 876 (1990) (citation omitted). In

Smith, the Supreme Court further held that neutral laws of

general applicability need not be justified by a compelling

governmental interest even when they have the incidental

effect of burdening a particular religious practice. Id. at

882-85, 110 S.Ct. 1595.

13

Under Smith, to withstand a challenge based on the Free

Exercise Clause of the First Amendment, a neutral state

law of general applicability that has the incidental effect

of burdening a particular religious practice need not be

justified by a compelling state interest, but need only

satisfy the rational basis test.

14

Aloha B&B does not

dispute that HRS Chapter 489 is a neutral law of general

applicability. However, it argues that we should depart

from Smith, impose a compelling state interest

requirement, and apply strict scrutiny in deciding its free

exercise claim under the Hawai‘i Constitution.

15

We need not decide whether a higher level of scrutiny

should be applied to a free exercise claim under the

Hawai‘i Constitution than the United States Constitution.

This is because we conclude that HRS Chapter 489

satisfies even strict scrutiny as applied to Aloha B&B’s

free exercise claim. To satisfy strict scrutiny, a statute

must further a compelling state interest and be narrowly

tailored to achieve that interest. Nagle v. Board of

Education, 63 Haw. 389, 392, 629 P.2d 109, 111 (1981)

(“Under the strict scrutiny standard ... [a] court will

carefully examine a statute to determine whether it

furthers compelling state interests and is narrowly drawn

to avoid unnecessary abridgment of constitutional

rights.”); Kolbe v. Hogan, 849 F.3d 114, 133 (4th Cir.

2017) (en banc) (“To satisfy strict scrutiny, ... the

challenged law [must be] ‘narrowly tailored to achieve a

compelling governmental interest.’ ” (citation omitted)).

In evaluating Aloha B&B’s free exercise claim under the

Hawai‘i Constitution, we balance the burden HRS

Chapter 489 imposes on Young’s free exercise of religion

**935 *193 against the State’s interest in prohibiting

discrimination in public accommodations. See Korean

Buddhist Dae Won Sa Temple of Hawaii v. Sullivan, 87

Hawai‘i 217, 246, 953 P.2d 1315, 1344 (1998). To

establish a prima facie case for its free exercise claim,

Aloha B&B must show that HRS Chapter 489 interferes

with a religious belief that is sincerely held by Young and

imposes a substantial burden on Young’s religious

interests. See id. at 247, 953 P.2d at 1345.

Aloha B&B asserts that based on Young’s religion, she

believes that sexual relations between individuals of the

same sex are immoral; that providing a room to a

same-sex couple would serve to facilitate conduct she

believes is immoral; and thus requiring her to provide

lodging to Plaintiffs and other same-sex couples would

impose substantial burdens on her free exercise of

religion. Plaintiffs have not challenged the sincerity of

Young’s religious beliefs, but argue that Aloha B&B

cannot show a substantial burden on Young’s religion.

Plaintiffs argue that Young’s religious beliefs do not

compel her to operate a bed and breakfast business. They

also assert that Young can still use her home to generate

income without any alleged conflict between her religious

beliefs and the law by relying on the “Mrs. Murphy”

exemption in HRS Chapter 515 and renting out rooms to

tenants seeking long-term housing.

Assuming, without deciding, that Aloha B&B established

a prima facie case of substantial burden to Young’s

exercise of religion, we conclude that the application of

HRS Chapter 489 to Aloha B&B’s conduct in this case

satisfies the strict scrutiny standard. As previously

discussed, Hawai‘i has a compelling state interest in

prohibiting discrimination in public accommodations. The

Hawai‘i Legislature has specifically found and declared

that “the practice of discrimination because of ... sexual

orientation ... in ... public accommodations ... is against

public policy.” HRS § 368-1 (2015). Discrimination in

public accommodations results in a “stigmatizing injury”

that “deprives persons of their individual dignity” and

injures their “sense of self-worth and personal integrity.”

Roberts, 468 U.S. at 625, 104 S.Ct. 3244; King, 656 P.2d

at 352, cited in Hoshijo ex rel. White, 102 Hawai‘i at 317

n.22, 76 P.3d at 560 n.22. Aloha B&B itself has

acknowledged that “in places of public accommodation

discrimination is a horrible evil.”

HRS Chapter 489 is narrowly tailored to achieve

Hawai‘i’s compelling interest in prohibiting

discrimination in public accommodations. See Roberts,

468 U.S. at 626, 104 S.Ct. 3244 (holding that Minnesota,

in applying its public accommodations statute to prohibit

the Jaycees from discriminating against women, advanced

its interest “through the least restrictive means of

Cervelli v. Aloha Bed & Breakfast, 142 Hawai‘i 177 (2018)

415 P.3d 919

© 2019 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

12

achieving its ends”). HRS Chapter 489 “responds

precisely to the substantive problem [of discrimination in

public accommodations] which legitimately concerns the

State.” Id. at 629, 104 S.Ct. 3244 (internal quotation

marks and citation omitted). Because the application of

HRS Chapter 489 to Aloha B&B’s discriminatory

conduct in this case satisfies even strict scrutiny, Aloha

B&B is not entitled to relief on its free exercise claim.

16

CONCLUSION

Based on the foregoing, we affirm the Circuit Court’s

Summary Judgment Order.

All Citations

142 Hawai‘i 177, 415 P.3d 919

Footnotes

1

The Honorable Edwin C. Nacino presided.

2

HRS Chapter 489 is entitled “Discrimination in Public Accommodations.” HRS § 489-3 (2008) provides:

Discriminatory practices prohibition. Unfair discriminatory practices that deny, or attempt to deny, a person the full and equal

enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, privileges, advantages, and accommodations of a place of public accommodation

on the basis of race, sex, including gender identity or expression, sexual orientation, color, religion, ancestry, or disability are

prohibited.

3

The only claim for which Plaintiffs and the HCRC did not seek summary judgment was the claim for damages in the Complaint.

4

As discussed infra, HRS § 489-2 defines “place of public accommodation” to include “[a]n inn, hotel, motel, or other

establishment that provides lodging to transient guests[.]”

5

The Circuit Court’s Order was entitled “Order Granting Plaintiffs’ and [the HCRC’s] Motion for Partial Summary Judgment for

Declaratory and Injunctive Relief and Denying [Aloha B&B’s] Motion for Summary Judgment,” which we will refer to as the

“Summary Judgment Order.”

6

HRS § 515-3 identifies numerous other actions related to real estate transactions that constitute “discriminatory practice[s].”

7

At the time that Plaintiffs attempted to secure lodging with Aloha B&B, HRS § Section 515-4(a)(2) (2006) provided:

(a) Section 515-3 does not apply:

...

(2) To the rental of a room or up to four rooms in a housing accommodation by an individual if the individual resides

therein.

Although HRS § 515-4(a)(2) (2006) was subsequently amended, the differences between the pre-amended and post-amended

statute are not material to our analysis in this case because Young was an owner/resident. For simplicity, we refer to the current

version of the statute in our analysis.

8

Because we conclude that Aloha B&B falls within the statutory definition of “place of public accommodation” as “an

establishment that provides lodging to transient guests,” we need not address whether the Circuit Court was correct in

determining that Aloha B&B also constitutes a place of public accommodation as “ [a] facility providing services relating to travel

or transportation.” See HRS § 489-2.

9

“Mrs. Murphy” was a hypothetical widow running a boarding house, whose circumstances were first cited in the 1960s to argue

that a person renting a small number of rooms in the person’s residence should be exempted from laws prohibiting

discrimination.

10

See Flores v. United Air Lines, Inc., 70 Haw. 1, 12 n.8, 757 P.2d 641, 647 n.8 (1988) (“Generally, remedial statutes are those which

provide a remedy, or improve or facilitate remedies already existing for the enforcement of rights and the redress of injuries.”

(internal quotation marks and citation omitted)).

Cervelli v. Aloha Bed & Breakfast, 142 Hawai‘i 177 (2018)

415 P.3d 919

© 2019 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.

13

11

Contrary to Aloha B&B’s contention, the doctrine of ejusdem generis does not support its claim that it falls outside the definition

of a “place of public accommodation.” See Richardson v. City and County of Honolulu, 76 Hawai‘i 46, 74, 868 P.2d 1193, 1221

(1994) (Klein, J., dissenting) (describing the doctrine of ejusdem generis to mean: “[W]here words of general description follow

the enumeration of certain things, those words are restricted in their meaning to objects of like kind and character with those

specified.”). The doctrine is inapplicable where the statute’s plain meaning is apparent or where applying the ejusdem generis

rule would conflict with other, clearer indications of the Legislature’s intent. United States v. West, 671 F.3d 1195, 1199 (10th Cir.

2012); Leslie Salt Co. v. United States, 896 F.2d 354, 359 (9th Cir. 1990). As we have concluded, the plain language of HRS Chapter

489 and the Legislature’s directive that it be liberally construed to further its anti-discrimination purposes clearly establishes that

Aloha B&B falls within the definition of a “place of public accommodation.” In any event, Aloha B&B’s claim that the ejusdem

generis doctrine supports its claim because a bed and breakfast operates out of a residence while an inn, hotel, and motel do not

is without merit. The trait that unifies the items in the list is set forth in the statutory definition itself - - establishments “that

provide[ ] lodging to transient guest.” It is undisputed that Aloha B&B possesses this unifying trait.

12

While Young stated that she will not accept reservations from smokers, same-sex couples, unmarried couples, and disabled

people who cannot climb the stairs, Young stated that the standard questions she asks people in processing a reservation

consists of the dates they want, whether they are smokers, what room they are asking about, requesting their names, addresses,

and contact information, asking if they have any dietary needs, and asking about the deposit. Therefore, based on her standard

questions, Young would not be able to determine the customers’ marital status or whether they are able to climb stairs.

13

The Supreme Court explained:

The government’s ability to enforce generally applicable prohibitions of socially harmful conduct, like its ability to carry out

other aspects of public policy, “cannot depend on measuring the effects of a governmental action on a religious objector’s

spiritual development.” To make an individual’s obligation to obey such a law contingent upon the law’s coincidence with his

religious beliefs, except where the State’s interest is “compelling” - - permitting him, by virtue of his beliefs, “to become a law

unto himself,” - - contradicts both constitutional tradition and common sense.

Smith, 494 U.S. at 885, 110 S.Ct. 1595 (citations and footnote omitted).

14

In response to the Supreme Court’s decision in Smith, Congress passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (RFRA),’

which prohibits government from substantially burdening the exercise of religion, even through a neutral law of general

applicability, unless the government can show that the law was in furtherance of a compelling government interest and was the

least restrictive means of furthering that interest. See City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507, 515-16, 117 S.Ct. 2157, 138 L.Ed.2d

624 (1997). In City of Boerne, however, the Supreme Court invalidated the RFRA as it applied to the States. Id. at 511, 536, 117

S.Ct. 2157. Thus, with respect to state laws, the Smith standard generally applies to claims under the Free Exercise Clause of the

First Amendment. See Korean Buddhist Dae Won Sa Temple of Hawaii v. Sullivan, 87 Hawai‘i 217, 246 & n.31, 953 P.2d 1315,

1344 & n.31 (1998).

15

Similar to the United States Constitution, the Hawai‘i Constitution provides: “No law shall be enacted respecting the

establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof ....” Haw. Const. art I, § 4 (emphasis added).

16

We reject Aloha B&B’s claim that Plaintiffs’ Complaint should have been dismissed for failing to name Young, who it maintains is

an indispensable party, as a defendant. Aloha B&B is operated as a sole proprietorship with Young as its sole proprietor. “[I]n the

case of a sole proprietorship, the firm name and the sole proprietor’s name are but two names for one person.” Credit Assocs. of

Maui, Ltd. v. Carlbom, 98 Hawai‘i 462, 466, 50 P.3d 431, 435 (App. 2002) (block quote format and citation omitted).

End of Document

© 2019 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works.