Working Paper

September 2019

Adis Dzebo

Hannah Janetschek

Clara Brandi

Gabriela Iacobuta

Connections

between the Paris

Agreement and the

2030 Agenda

The case for policy coherence

Stockholm Environment Institute

Linnégatan 87D 115 23 Stockholm, Sweden

Tel: +46 8 30 80 44 www.sei.org

Author contact: Adis Dzebo

Editing: Karen Brandon

Layout: Richard Clay

Cover photo: Douglas Sacha / Getty

This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational

or non-profit purposes, without special permission from the copyright holder(s) provided

acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or

other commercial purpose, without the written permission of the copyright holder(s).

Copyright © July 2019 by Stockholm Environment Institute

Stockholm Environment Institute is an international non-profit research and policy

organization that tackles environment and development challenges.

We connect science and decision-making to develop solutions for a sustainable future for all.

Our approach is highly collaborative: stakeholder involvement is at the heart of our eorts

to build capacity, strengthen institutions, and equip partners for the long term.

Our work spans climate, water, air, and land-use issues, and integrates evidence

and perspectives on governance, the economy, gender and human health.

Across our eight centres in Europe, Asia, Africa and the Americas, we engage with policy

processes, development action and business practice throughout the world.

Contents

Abstract ................................................................................................ 4

1. Introduction ....................................................................................4

2. Connecting two separate global processes through

coherent national implementation............................................5

2.1 The Paris Agreement and the Agenda 2030 ............................5

2.2 Connecting the two agendas through policy coherence ..6

3. Methodology...................................................................................7

4. 2030 Agenda through a climate lens – main findings for

how climate action complements the SDGs .......................... 9

4.1 The top tier: SDGs with the strongest connections to

NDC activities .......................................................................................10

4.2 The middle tier: SDGs with mid-level connections to NDC

activities ....................................................................................................19

4.3 The bottom tier: SDGs with few connections to NDC

activities ...................................................................................................27

5. Discussion ................................................................................... 28

5.1 NDCs are more than climate action plans .............................. 28

5.2 NDCs need to be complemented and strengthened ........29

5.3 Opportunities for increased policy coherence ...................30

6. Conclusions and next steps ..................................................... 31

References .........................................................................................32

4 Stockholm Environment Institute

Abstract

Finalized in 2015, the Paris Agreement and the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable

Development both represent universally approved policy visions that signal a paradigm shift:

from a “top-down” approach of set, international mandates to a “bottom-up”, country-driven

implementation process. Limited interaction between the processes of the two agendas at both

global and national levels, however, threatens to impede eective implementation. Furthermore,

aggregate analyses are lacking to enhance understanding of potential overlaps, gaps and conflicts

between the two agreement’s key implementation instruments: the Nationally Determined

Contributions (NDCs) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Such analyses are

essential to increase policy coherence of plans and strategies, and to improve eectiveness of

implementation of the two agendas. This paper aims to fill this gap. It provides a global analysis

that explores how the climate actions contained in countries’ NDCs connect to the 17 SDGs. The

paper, which builds on the findings of the NDC-SDG Connections tool, demonstrates that NDC

actions to various extents foster synergies with national development priorities that reflect the 2030

Agenda. The research further reveals those sustainable development-related issues that are directly

addressed through climate action, and those issues that are currently absent from NDC activities.

The paper demonstrates that the actions outlined in the NDCs to various extents foster synergies

with national development priorities that reflect the 2030 Agenda. We find that a large number of

climate activities support, for example, SDG 7 (aordable and clean energy), SDG 15 (life on land)

and SDG 2 (zero hunger), but that significant gaps exist in relation to SDGs such as SDG 5 (gender

equality), SDG 1 (no poverty) and SDG 16 (peace and justice). Increasing the transparency and

understanding of these possible connections, gaps and conflicts can facilitate policy coherence and

leverage buy-in for ambitious implementation of the two agendas.

1. Introduction

The Paris Agreement and 2030 Agenda both represent internationally agreed, universal visions.

Their implementation is based on a “bottom-up” process, meaning that countries identify and

subsequently act and report on their own priorities, needs and ambitions (Mbeva and Pauw

2016; Carraro 2016). This paradigm shift towards governance by goals, targets and contributions

set by individual countries, as opposed to a “top-down” approach of set international mandates

has created a debate in academia as well as in policy-making circles about how to coherently

implement both agendas (Biermann et al. 2017, Bouyé et al. 2018, Janteschek et al. 2019; Roy et

al. 2018). Horizontal policy coherence thus represents a key challenge. How can national climate

policy be truly ambitious over the medium and long terms while also cohering with other important

policy targets and objectives adopted by a government? At present, two processes are taking

place in parallel with limited, if any, communication on the interfaces between them (UNDP 2017).

Policy agendas are being set through two distinct channels: 1) National Sustainable Development

Strategies (NSDS’s) intended to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the

2030 Agenda, and 2) the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) intended to achieve the

aims of the Paris Agreement

This situation raises issues related to the crafting and implementing of policies that can achieve the

ambitious objectives of sustainability and climate change missions. These aims require knowledge

about thematic alignments and potential goal conflicts, not only within but also between the two

agendas (Lyer et al. 2018; Von Stechow et al. 2015). For example, can energy access for all be

secured without relying on fossil fuels? Can climate adaptation be pursued in an inclusive way in

unequal societies? Research on both the conceptual and empirical connections between the two

agendas is emerging (see e.g. Pahuja and Raj 2017; UNFCCC 2017; Iacobuta et al. 2018; Huang 2018;

GIZ 2018; Nguyen et al. 2018; Janteschek et al. 2019; Northrop et al. 2016). However, aggregate

analysis is lacking to enhance understanding of overlaps and gaps between NDCs and SDGs

that can increase policy coherence of plans and strategies, and to improve eectiveness of the

implementation of both the Paris Agreement and the Agenda 2030. This paper aims to fill this gap.

In light of the

multiple overlaps,

the assessed NDCs

can be regarded

not only as climate

plans but also as de

facto sustainable

development

plans because

they include many

priorities that reflect

the 2030 Agenda.

Connections between the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda 5

It provides a global analysis of countries’ NDCs, and explores how climate actions connect with the

broader sustainable development agenda. The paper uses NDC-SDG Connections,

1

an interactive online

tool that highlights thematic contributions of NDCs to the 2030 Agenda (Brandi et al. 2017), and reveals

areas related to sustainable development that are not included in countries’ climate action plans.

Section 2 of this study explores the two historical processes that led to the Paris Agreement and the

2030 Agenda. Section 3 discusses our methodology. Section 4 presents the results of the analysis

of possible NDC-SDG connections, and dierentiates SDGs according to whether they have high,

medium or low levels of connections with climate action. This section shows which climate actions are

most relevant to the broader sustainability agenda, and it identifies themes that should be made more

complementary to climate action through more adequately designed NSDS’s. Section 5 then discusses

the ways forward to meaningfully align the thematic implementation of both agendas (the 2030 Agenda

and the Paris Agreement). Section 6 concludes by setting out next steps for research and analysis.

1 http://ndc-sdg.info/

2 http://unfccc.int/focus/ndc_registry/items/9433.php

3 From here on, for consistency, we only use the term “NDC”.

4 Subsequently, we use the abbreviation “NSDS’s” to encompass all types of national and subnational strategies to implement the

SDGs.

2. Connecting two separate global processes through

coherent national implementation

2.1 The Paris Agreement and the Agenda 2030

In 2013, the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) decided that

each member state would submit a national climate plan, so called Intended Nationally Determined

Contributions (INDCs), as the core mechanism for increasing climate ambition. This decision,

representing a shift from the Kyoto Protocol process, created a bottom-up approach for the Paris

Agreement. Countries are free to determine their own climate targets and instruments, expressed in

nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Once a country ratifies the Paris Agreement, its INDC

converts into an NDC. Many countries have already formally joined the Paris Agreement and converted

their INDCs to NDCs, while a few countries have chosen to revise their INDC in the conversion

process.

2

Under the provisions of the Paris Agreement, each country submits an updated every five

years, with the aim of ratcheting up ambition compared with the previous NDC.

3

The success of the

Paris Agreement can be attributed to – and will depend on – these strategic documents. While initially

intended to be documents outlining commitments to greenhouse gas reduction, the 165 submitted

NDCs representing 192 Parties go far beyond the proposal to reduce emissions to mitigate climate

change; they also mention numerous adaptation measures as well as other activities that promote

sustainable development (Pauw et al. 2016).

The 2030 Agenda encompasses 17 SDGs (Figure 1), 169 targets and a declaration text articulating the

principles of integration, universality, transformation and a global partnership. The agenda came into

being through a unique global process of an open working group, which jointly developed the 17 SDGs

that were subsequently agreed on by all UN member states (Beisheim 2015). The SDGs include the

social, environmental and economic dimensions of development. They aim to provide a social foundation

for humanity while ensuring that human development takes place within earth’s biophysical boundaries

(Rockström 2009). At national levels, implementation of the 2030 Agenda varies from country to

country, and is based on national needs and ambitions. At the international level, the High-Level Political

Forum (HLPF) meets annually under the auspices of the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC)

to discuss Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs) as part of the oicial follow-up and review mechanism

of the 2030 Agenda (Beisheim 2018). However, individual countries are left to set-up an institutional

architecture for implementing the SDGs at national and subnational levels through National Sustainable

Development Strategies (NSDS’s)

4

. Countries can also work in partnership with other countries to learn

from each other’s experiences on challenges in implementation.

6 Stockholm Environment Institute

The Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda rest on an architecture which can be described

as “hybrid multilateralism” as it splices together state and non-state actions both in the state-

defined contributions to the agreements as well as in the eorts initiated by UN organizations

to orchestrate actions to reach the goals of the agreements (Bäckstrand et al. 2017). Their

implementation is based on countries identifying, and subsequently acting and reporting on

their own priorities, while non-state actors are formally expected to participate in overseeing

and facilitating the implementation (Bäckstrand et al. 2017). However, dierent institutional,

policy and administrative processes, dierent actors, and dierent datasets have been utilized

to translate the global commitments of the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement into national

frameworks, institutions and actions (UNDP 2017). There is institutional fragmentation (Biermann

et al. 2017) in the governance of climate change and sustainable development (Gupta and van der

Grijp 2010), both at the global and the national level that impose an extra obstacle to coherent

implementation processes.

To increase coherence in the implementation of these two agendas, more knowledge is needed,

both at the global level and in national contexts. One approach to this end is to investigate

the links between the NDCs and the SDGs. While NDCs are primarily a mechanism for climate

action, many countries have used them to indicate other priorities and ambitions for sustainable

development (Pauw et al. 2016). Individual NDCs are very dierent in scope and content to SDGs,

and the SDGs were still being negotiated when countries were developing their NDCs; thus, the

thematic areas through which NDCs address various SDGs are not clearly indicated, and further

analysis is needed.

2.2 Connecting the two agendas through policy coherence

Understanding the connections between climate change and sustainable development is a

first step needed to foster coherency of implementation of both agendas. The concept of

policy coherence is commonly defined as matching of policies, processes and institutions at all

government and governance levels to avoid contradictions and goal conflicts in policy making.

Policy coherence in sustainable development addresses the systematic integration of policies,

processes and institutions towards coherent implementation of sustainable development (OECD,

2018: 83; OECD 2001; ICSU 2017). Its importance is reflected in SDG 17.14 (enhance policy

coherence for sustainable development), making it a key objective of the 2030 Agenda.

Figure 1: The 17 Sustainable Development Goals

Source: United Nations

Connections between the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda 7

Policy coherence means that the combined policies addressing an area are compatible,

mutually reinforcing or even synergistic, while incoherence means that they are conflicting or

contradictory (May et al. 2006). For example, in the case of energy, policy coherence is a useful

concept for understanding to what extent energy policy goals and other policy goals (economic,

environmental, social) mutually support or undermine one another (Meuleman 2019; Tosun et al.

2017). Policies promoting electrification in rural areas (as one type of energy policy) can also help

to improve rural infrastructure and therefore help to further SDG 4 that calls for inclusive and

equitable education. On the other hand, if electrification is achieved through scaling-up of fossil

fuels, trade-os can arise with other goals or targets. Thus, evaluation of policy measures related

to energy systems would need to consider their eects both on SDG 7 (aordable and clean

energy) as well as on sustainable development more broadly (McCollum et al. 2018).

There have been calls to expose and mediate goal conflicts at an early stage for coherent

implementation within political and socio-economic contexts in the short and long terms, at all

levels of implementation, and across regions (OECD 2016; Kanter et al. 2016). For example, the use

of biofuels for energy production would likely reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but could also

negatively aect food prices through competition over land resources used for food production.

Biofuels could harm ecosystems and biodiversity through increased expansion of monocultures.

Biofuels would also likely aect soil and water through use of fertilizers and pesticides if these

risks are not adequately addressed in the policy design (see e.g. Hasegawa et al. 2018; Bonsch et

al. 2016). Thus, in this case, progress towards achieving SDG 7 could negatively harm progress

towards achieving SDGs 2 (end hunger/promote sustainable agriculture), 6 (clean water and

sanitation) and 15 (life on land/restore and protect ecosystems).

Analysing the potential impact of NDCs on SDGs allows insights into overlaps and gaps between

the implementation of the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda. This relationship is diicult to

trace, however, because trade-os are most often not mentioned in policy documents, and they

are not formulated as direct actions. For a coherent implementation of the two agendas, adequate

methods to identify trade-os need to be developed, and an improved understanding of such

interactions is required to manage potential goal conflicts and inconsistencies among economic,

social and environmental policy objectives.

5 The lone exception is the Iraqi NDC, which was published in Arabic only. The 27 member states of the European Union all

share one NDC, despite being individual parties to the Paris Agreement. This means that the same data will be presented for

these countries.

3. Methodology

The analysis in this paper focuses on understanding how NDCs address various SDGs beyond

climate action. To do so, we use the NDC-SDG Connections tool (Brandi et al. 2017) to identify

how NDC activities and targets relate to SDGs. The analysis behind the NDC-SDG connections

presented here is based on a textual analysis of all NDCs or INDCs that were available in 2016.

5

To create the database, the textual content of each NDC was examined to identify concrete

“activities” – statements presenting a strand of future activity, conditional or unconditional, under

the NDC. These disaggregated activities served as data points for the analysis. These activities

were subsequently matched with one of the 17 SDGs. An activity description usually ranges

between a minimum of one sentence and a maximum of three sentences. Where a statement

applies to multiple SDG targets (as was the case for only a very limited number of activities, it was

added to the database multiple times. In cases, where SDG targets overlap in their definition, we

assigned an activity to only one of them (e.g. education in SDG 4.7 and SDG 13.3). We started by

counting the frequency of key words as well as the volume of committed activities of a country

in a certain policy sector. Coding stuck very much to the exact wording of the activity, but

hand coding also was used to define close synonyms of certain activities (e.g. “water storage

capacities” were coded as “infrastructure”). We coded the data points (NDC activities) for all 17

SDGs and their 169 targets in four broad categories:

At present, two

processes are taking

place in parallel

with limited, if any,

communication

on the interfaces

between them.

8 Stockholm Environment Institute

1. Interpretation: Assessment of NDC activities according to their radius of influence (national,

regional, local); type of climate action (adaptation, mitigation, both, or none); whether the

activities imply capacity-building measures; whether the activities imply technological

improvements (and if so, the type of technology); whether the activity mentions a quantifiable

target to be reached; and whether the activity relates to a policy plan or strategy (and if so at

what level).

2. SDG targets: Here we assessed whether a climate activity can be linked to specific SDG

targets in their wording. For this purpose, we created a codebook that includes the wording

of each SDG and its targets and also includes the oicial global indicators that follow

each target.

3. Climate actions: We derived, inductively from the NDC activities, a set of the most frequently

mentioned categories of action that could be attributed to the SDGs and SDG targets. This

set of so-called climate actions varies for each SDG.

4. SDG themes/Cross-cutting themes: We also looked for broader socio-economic sectoral

categories. Some themes closely relate to a particular SDG, but they can also be broader

than one SDG, and may encompass two or even more SDGs (e.g. agriculture as a theme

encompasses SDG 2 [zero hunger] and SDG 15 [life on land]). This approach helped reveal

co-benefits indicated in the climate activities that go beyond a specific SDG. For example, if

an activity targeted improvement in the agricultural sector it was coded as relevant for SDG

2.4 (maintain diversity of seeds, plants, animals], but if it also mentioned co-benefits for water

eiciency (SDG 6.4) and forest management (SDG 15.2) it was coded as providing co-benefits

on these respective SDG targets. In total, we identified 42 cross-sectoral categories, which we

analysed across all 17 SDGs.

Overall, from 164 NDCs, we derived more than 7,100 activities. These activities were then used as

data inputs for constructing the tool. To guarantee the reliability of our analysis we applied inter-

coder reliability, meaning that always at least two independent coders went through the data

material while a third final approval of the decisions taken was guaranteed for all the activities in

the analysis.

One limitation of our analysis is that it does not address co-benefits and trade-os that cannot

be directly linked to the wording of the NDC climate activity alone. In that sense, a single climate

activity would likely have a multitude of direct and indirect co-impacts on other SDGs, but we

indicate only the SDG most directly addressed. Hence, we analyse only direct links, not indirect

co-impacts. While this approach is powerful in identifying the strongest links and highlighting

the sustainable development dimension of the NDCs and overlaps and gaps between the two

agendas, it has the limitation of showing only positive interlinkages. More analysis is required to

tackle this dimension to complement the focus and capacity of the tool. Moreover, there is a need

to complement the current analysis of countries’ NDCs through the SDG-lens with an analysis

of their Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs), in which they report on their progress regarding the

2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and their links to the NDCs.

Connections between the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda 9

4. 2030 Agenda through a climate lens – main findings

for how climate action complements the SDGs

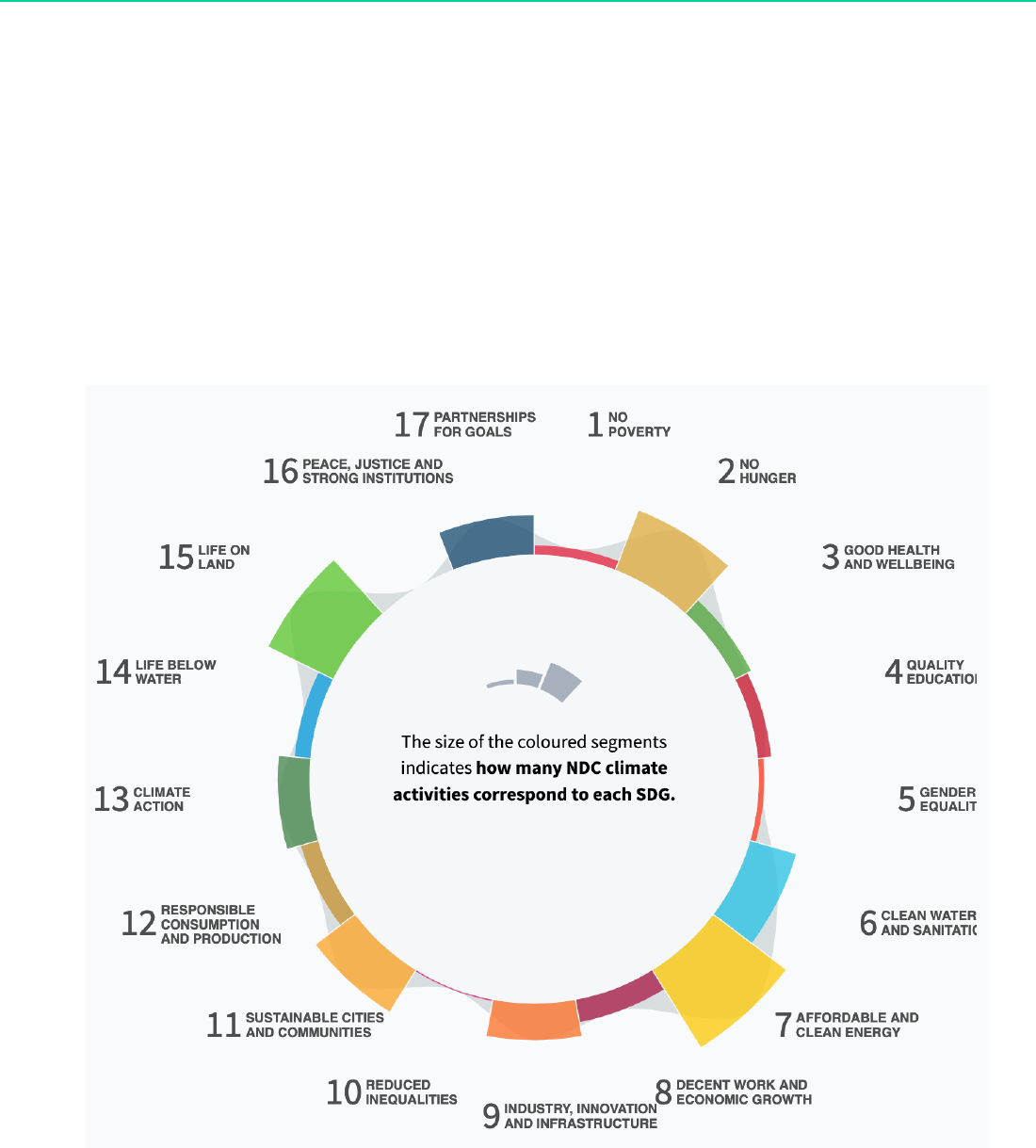

This chapter presents results from NDC-SDG Connections. The analysis of 164 NDCs reveals

strong connections between climate ambition and the broader sustainable development agenda

(Figure 1). It shows, however, that not all SDGs are equally addressed by climate action. This

chapter is structured as follows: Chapter 4.1 presents SDGs that have strong connections with

climate activities ; Chapter 4.2 presents SDGs that have medium connections, and Chapter 4.3

presents SDGs that have hardly any overlap with climate activities.

Figure 2: Distribution of NDC activities in relation to the 17 SDGs

Source: ndc-sdg.info

10 Stockholm Environment Institute

4.1 The top tier: SDGs with the strongest connections to NDC

activities

Analysis from the NDC-SDG Connections reveals that proposed activities in countries’ NDCs

most prominently cover six SDGs. Many climate activities commit to increase renewable energy

sources and provide for more eicient energy technologies. Our research shows that six SDGs

have the strongest connection to NDC activities. Ordered from those with the strongest to the

weakest links, these six SDGs are:

• Aordable and clean energy (SDG 7) links access to energy and energy

eiciency measures to the key climate change objective to reduce greenhouse

gas emissions.

• Life on land (SDG 15) reflects the role of ecosystems, forest management and

land use in climate change mitigation and adaptation.

• No hunger (SDG 2) makes clear that sustainable and climate-smart agriculture

is seen as a key solution in the fight to limit average temperature increase to

below 2°C.

• Sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11) relates to climate activities focused

on urban planning and public transport.

• Clean water and sanitation (SDG 6) relates to climate activities focusing on

water eiciency and water ecosystem management.

• Partnerships for goals (SDG 17) highlights the importance of providing financial

support, technology transfer, and capacity building for those countries that

need it the most - particularly the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and the

Small-Island Developing States (SIDS).

Strongest links to NDC activities: aordable and clean energy (SDG 7)

As dependence on fossil fuels for energy production is a key driver of climate change (IPCC

2014), changing energy systems is at the center of mitigation activities of NDCs and hence

these activities contribute most prominently to SDG 7 (aordable and clean energy). Most

countries flag renewable energy and energy eiciency as key climate actions in their NDCs,

making SDG 7 the strongest point of connection with national climate plans. In that regard,

SDG 7 connects with the highest share of NDC activities, 16% of the total.

Figure 2 shows how NDC activities connect with SDG 7. The inner circle of the figure displays

how NDC activities connect with the respective targets of SDG 7. At the level of targets, more

than 50% of NDC activities relate to SDG 7.2 (increase substantially the share of sustainable

energy in the global energy mix), while 34% contribute to SDG 7.3 (double the global rate of

improvement in energy eiciency). In the outer circle of the figure, we show the frequency

(signified by the size of the segment) of specific climate actions attributed to that goal. In

terms of specific climate actions, they correspond well with the SDG targets. Energy eiciency

and clean and renewable energy are most important climate actions. In terms of specific energy

sources, solar energy is the most popular renewable source of energy, followed by hydropower

and bioenergy. Another key climate action is increasing energy eiciency measures (Figure 2).

For many low-income countries, however, the issue of high costs of renewable energy often

has to be balanced with the need for increased energy access. Achieving the global goal of

Connections between the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda 11

universal access to energy by 2030 in the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) will require a

350% increase in their annual rate of electrification. While on average 10% of people in other

developing countries lack access to electricity, in LDCs this remains the case for more than

60% of the population (UNCTAD 2017). Thus, for the LDCs, implementing SDG 7 is mainly about

energy access, and less about how to mitigate emission levels. While most renewable energy

sources have historically been more expensive than fossil fuels, the price gap has narrowed

rapidly in recent year and in some cases, it has even reversed (IRENA, 2018).

Dependence on fossil fuels for energy generation is a major driver of climate change and one

of the biggest climate-related challenges (Rogelj et al. 2015). However, energy is central to

multiple aspects of sustainable development (McCollum et al. 2018). For example, increased

energy eiciency has the potential to create multiple co-benefits for social progress, and

to enhance economic productivity (SDG 8). Moreover, the expansion of renewable energy

production could help jointly fulfil SDG 7 and tackle climate change (SDG 13), but also improve

health (SDG 3) through reduced air pollution (Braspenning Radu et al. 2016) and create

new decent jobs (SDG 8) (Fankhauser et al. 2008). However, there are also important trade-

os – as evidenced, for example, by the role of wood as both an energy source and carbon

sink (Cannell 2003), and by the potential competition over whether to use land to produce

biofuels for energy or for food (central to the SDG 2 to achieve zero hunger) (Hasegawa et

al. 2018). Moreover, hydropower may enhance achieving increase access to energy (SDG 7.1),

and, at the same time, risks increasing competition for water resources (SDG 6) and, through

the building of dams, hurting informal land title holders and marginalized people (SDG 1)

(Winemiller et al. 2016.).

Figure 3: Links between NDC activities and SDG 7 (aordable and clean energy)

Source: ndc-sdg.info

12 Stockholm Environment Institute

Given the important role of the energy sector in tackling GHG emissions, it is not surprising that

most (97%) NDC activities addressing SDG 7 are climate change mitigation activities. However,

the essential role of increased energy access for climate adaptation and the potential of o-grid

renewable sources to provide such access should not be ignored in countries with low energy

access and high risk of climate change impacts. Beyond this, only 31% of the climate activities we

identified provide for quantifiable mitigation targets. In future updates of NDCs, we see room for

improvement to raise the bar for quantifiable targets.

Second-strongest links to NDC activities: life on land (SDG 15)

SDG 15 (life on land) ranks second in terms of links to NDC activities. It calls for protecting,

restoring and promoting the sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems. Climate change is a major

driver of terrestrial ecosystem degradation, particularly desertification and biodiversity loss; at

the same time, deforestation, unsustainable land use activities, and biodiversity loss, in turn, drive

climate change. Forests and soils are major carbon sinks and can be used as powerful tools for

climate change mitigation and integrated land-use activities to foster land degradation neutrality

(UNCCD 2017). Activities in countries’ NDCs have a strong focus on issues related to SDG 15,

with 13% of the total number of activities related to this SDG. The most important climate actions

for SDG 15 are forest management, ecosystem conservation and biodiversity, and aorestation.

Several countries also highlight the importance of reducing emissions from deforestation and

forest degradation (REDD+) activities for forest management. Beyond actions concerning forests

and biodiversity, countries are also proposing softer measures, such as development of national

parks and prevention of wildfires and land erosion (Figure 3).

Figure 4: Links between NDC activities and SDG 15 (life on land)

Source: ndc-sdg.info

Connections between the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda 13

However, climate mitigation activities that can be attributed to SDG 15 do not automatically foster

sustainable development. Large-scale infrastructure projects, for example, can create severe

trade-os between climate change and sustainable development. With regards to REDD+, there is

a lack of coherence between political goals and their translation into institutional structures and

administrative processes. Whereas all mitigation approaches support sustainable development,

there are few related global regulations or requirements, and those that exist are largely voluntary

(Horstmann and Hein 2017).

In terms of SDG targets, more than half of the activities relate to SDG 15.2 (sustainable forest

management, and halting deforestation). In addition, SDG 15.1 (conservation, restoration and

sustainable use of terrestrial and inland freshwater ecosystems) and SDG 15.3 (restoring

degraded land and combating desertification) are related to significant numbers of activities. In

the context of SDG 15, there are thus many potential synergies between the implementation of

the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda. However, there are also gaps. Intended climate action

fail to address issues surrounding species protection, invasive species and genetic resources,

which are all important for achieving this goal. Furthermore, SDG 15 allows for opportunities

to reach out to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in order to

complement its work on ecosystem restoration (Bridgewater et al. 2015). This has largely been

ignored in the NDCs.

In addition to the direct climate connections, several issues such as combating deforestation and

land erosion, which are prominent in the NDC activities for this goal, have important connections

with other SDGs, particularly SDG 2 (no hunger), SDG 14 (life below water), and SDG 6 (water

and sanitation), in which the protection of mangroves and ecosystem resilience are synergetic

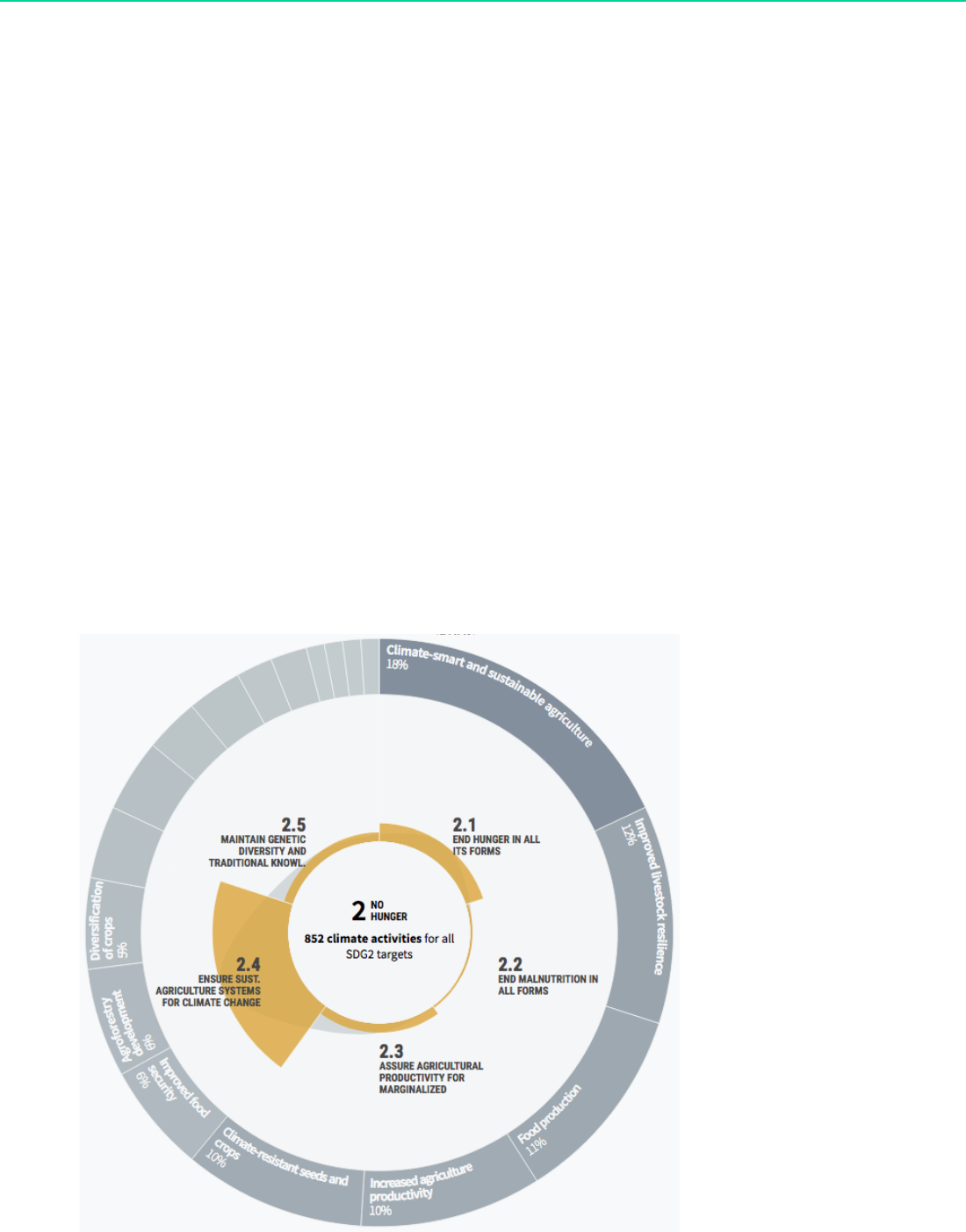

Figure 5: Links between NDC activities and SDG 2 (no hunger)

Source: ndc-sdg.info

14 Stockholm Environment Institute

elements. This indicates that systems of soil, water and biodiversity are intrinsically linked, and

need to be balanced with water, energy and food security to achieve an integrated law-carbon

and climate-resilient sustainable development pathway (Leininger et al. 2018, Müller et al. 2015a).

NDC activities under SDG 15 address climate change mitigation and adaptation in almost equal

numbers (adaptation, 35%; mitigation, 29%; adaptation and mitigation, 22%). Resilient forests and

natural ecosystems are critical to climate change adaptation of communities who benefit from

their ecosystem services. Moreover, while forests and natural ecosystems play the role of carbon

sinks, regulating the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, they could also

become a source of emissions when land-use change takes place. Beyond this, only 15% of the

climate activities that can be attributed to SDG 15 contain quantifiable measures. This illustrates

once more the room for improvement in the process of updating NDCs to enhance quantification

of what can be achieved in the forest and land-use sector to contribute to halting climate change

(Minasny et al. 2017, Lal 2016).

Third-strongest links to NDCs activities: no hunger (SDG 2)

SDG 2 (no hunger) ranks third in terms of the number of connections with NDCs. SDG 2 is

connected to the third-largest share (13% of the total) of NDC activities. Ending hunger,

achieving food security, improving nutrition, and promoting sustainable agriculture lie at the

core of this SDG. But most of the activities for SDG 2 center on climate-smart agriculture:

developing the technical, policy and investment conditions to increase food security and

agricultural incomes through climate-resilient, low-emission agriculture (Figure 4). Climate-

smart agriculture is at the core of countries’ climate ambitions to end hunger; this makes it both

a prominent climate action and at prominent matter for sustainable development, as evidenced

by SDG 2.4 (ensuring sustainable agriculture systems for climate change (Lan et al. 2018,

FAO 2016). However, while climate-smart agriculture is being championed by the UN’s Food

and Agriculture Organization (FAO) as the main pathway to reducing emissions and building

resilience in agriculture (FAO 2016), it is also a contested area in which civil society, international

organizations and transnational corporations aim to control the discourse over production,

finance and technology (Newell and Taylor 2018; Clapp et al. 2018).

Eects of climate change can have severe impacts on agricultural production and, hence,

on food production and food security. This is evident in countries’ NDCs, which signal the

importance of climate actions related to food production and improved food security, livestock

resilience, and climate-resistant seeds and crops. On the other hand, few activities relate to

SDG 2.2 (end malnutrition), SDG 2.3 (assuring productivity for the marginalized) or SDG 2.5

(maintaining genetic diversity and traditional knowledge). These issues, together with land

rights and livelihoods for farmers, need to complement SDG 2 ambitions, illustrating the need

for countries’ climate ambitions to be complemented with other national development plans and

strategies to meaningfully integrate both agendas in implementation at the national level.

Climate actions that focus on making agricultural production more sustainable also create

co-benefits for improved water management (SDG 6), raising the need for irrigation; drought-

resistant seeds and integrated water resource management; land-use management and forestry

(SDG 15) through soil management, livestock and agroforestry; and economic growth (SDG 8)

through improved livelihoods.

NDC activities that address SDG 2 mostly tackle climate change mitigation (60%), reflecting

the large share of global greenhouse gas emissions attributed to this sector. However, as the

impacts of climate change begin to be felt more strongly, resilience of agricultural systems

becomes a critical element in ensuring food security around the world. Only 10% of NDC

activities assigned to SDG 2 address climate change adaptation, and just 21% address both

adaptation and mitigation. Moreover, only 7% of the climate activities provide for quantifiable

emission reduction targets. Given the immense attention that was brought to the role of

Connections between the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda 15

agriculture through the “4 per 1000” Initiative

6

to halt climate change in 2015, there may be

opportunities to learn how to best increase the number of commitments that can be quantified.

6 See https://www.4p1000.org/ for further information.

Fourth-strongest links to NDCs activities: sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11)

SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities) ranks fourth in terms of the number of links with

NDCs. SDG 11 calls for making cities and other human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and

sustainable, and aims at improving access for all to housing, public spaces and basic services,

while improving urban planning to guarantee a more sustainable urbanization process. This

reflects and underscores the importance of cities and communities when it comes to halting

climate change (WBGU 2016). More than 70% of all greenhouse gas emissions are generated by

cities (Seto et al. 2014). Moreover, cities are often highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate

change and natural disasters more generally. Cities – and the global urbanization trend – play a

central role in achieving sustainable development worldwide and are of particular relevance to

the prospective success of both the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda (Brandi 2018).

SDG 11-related issues are present in 9% of total NDC activities and 82% of all NDCs include

urbanization-related climate activities. At least one NDC activity relates to each of the targets

under this SDG, but the most prominent targets are SDGs 11.2 (accessible and sustainable

transport systems), 11.5 (disaster risk management) and 11.3 (integrated urban planning).

Commitments to clean fuels, public transport, electric vehicles as well as focus on low carbon

intensive transport via ship and railway are at the core of climate actions that pay into SDGs

Figure 6: Links between NDC activities and SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities)

Source: ndc-sdg.info

16 Stockholm Environment Institute

11.2 and 11.3, while early warning systems emphasize climate action towards SDG 11.5 (Figure

5). NSDS’s to implement the SDGs could meaningfully complement this transport supply

commitment with transfer schemes to increase access and willingness to use public transport

systems and reduce the number of private vehicles which in return has valuable repercussions for

achieving other SDGs at the same time.

If current urban construction trends continue, limiting global warming to 2°C will be nearly

impossible. Hence, it is not surprising that climate activities have a major focus on cities, and

on issues such as clean transport and air quality. However, given the ongoing trend of emerging

megacities and urbanization of small- to medium-size cities, climate activities could improve

by focusing more on planning that anticipates (informal) settlements and community-based

development issues. If NDCs make integrated urban planning the focus of their commitments, a

more planned process could replace processes that instead adjusting to continuously worsening

situations in emerging medium-size and mega-cities. Transformative urbanization policies can

help to implement both the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda (WBGU 2016). SDG 11-related

issues such as transport, infrastructure and disaster risk management link up with several other

SDGs. For instance, new and renovated infrastructure in cities would have to take into account

requirements under SDG 9 (industry, innovation and infrastructure), while measures to address

potential flooding and other water-related disasters in cities would touch upon SDG 14 (life below

water). SDG 11 has a strong cross-cutting character and contributes to a multitude of SDGs, due

to the complexity and spread of cities.

Cities are expected to provide housing for 68% of the world population by 2050 (UN Habitat

2016), requiring substantial investments for adaptation and climate-proof expansion. Moreover,

as indicated above, cities make up for 70% of all greenhouse gas emissions (Seto et al. 2014).

Therefore, a large share of climate change mitigation activities is expected to take place in cities,

and these can be closely linked to transport system changes (mitigative measures) as well as

disaster risk management (adaptive measures). It is, therefore, not surprising that NDC activities

attributed to SDG 11 tend to tackle climate change mitigation and adaptation in comparable

amounts – 35% adaptation, 47% mitigation, and 17% adaptation and mitigation concurrently.

Beyond this, only 11% of the commitments are quantifiable in their nature of commitment.

Considering the large share of mitigation activities, we see room for improvement especially in the

transport sector, for NDCs to raise ambitions towards more quantifiable emission reduction and

creation of co-benefits for example health through reduction of air pollution.

Fifth-strongest links to NDCs activities: clean water and sanitation (SDG 6)

SDG 6 (clean Water and sanitation) contains targets on resource eiciency, water governance,

transboundary management, and provision of sanitation for all. Transition towards a low-

carbon and climate-resilient society will increase the multiple demands on both water and land

resources (Müller et al. 2015a). Hence, climate change is closely intertwined with the availability

of and demand for water resources. For instance, climate change and extreme weather events

can intensify water scarcity, especially in countries where access to water is already an issue –

making water resource management an important element of adaptation (World Water Council

2018). At the same time, climate change-related flooding can spread water-borne pollution and

diseases, particularly in areas with poor sanitation infrastructure.

In total, 630 NDC activities, equaling 9% of the total number of activities. They relate mainly to

improving water management and increasing eiciency in water supply. At the level of targets,

SDG 6.4 (increase water-use eiciency across all sectors) is the most commonly addressed in

climate activities. Thus, most activities related to SDG 6 focus on water, while sanitation fails

to attract the same level of attention. For example, SDG 6.2 (equitable access to sanitation and

hygiene) receives least attention of the six targets (Figure 6). Room for improvement can be seen

in regard to wastewater treatment; this is an issue area that has potential to address water sector

Connections between the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda 17

mitigation, and, at the same time, to decrease stress in many countries worldwide that face stress

from high pollution levels. Household-level provision of sanitation facilities as such is not in the

radius of climate activities, even though such provision can be an element that meaningfully

complements climate activities when implementing the SDGs at national level.

Achieving SDG 6 is also crucial to achieve multiple other SDGs, such as food security (SDG 2),

health and well-being (SDG 3) and poverty eradication (SDG 1). Beyond these co-benefits from

water activities, water resources are needed as an input to achieve multiple other SDGs, such

as renewable energy from hydropower (SDG 7) (Dombrowsky and Hensengerth 2018, Ringler et

al. 2013, Weitz et al. 2014) as well as responsible production of raw materials and substitutes for

plastic (SDG 12) (Müller, et al. 2015b).

SDG 6 mainly consists of adaptation measures (87%), with only 3% of activities relating to mitigation.

Increasing mitigation opportunities from the water sector remains a relatively untouched issue area

in both academia and policy. However, water management’s impact on greenhouse gas emissions is

not irrelevant. For example, irrigation systems are both energy intensive and require more fertilizer

than most rainfed systems (Siebert et al., 2010). Furthermore, sewage treatment can be a major

source of methane emissions, but this can also be captured as biogas (Never and Stepping 2018).

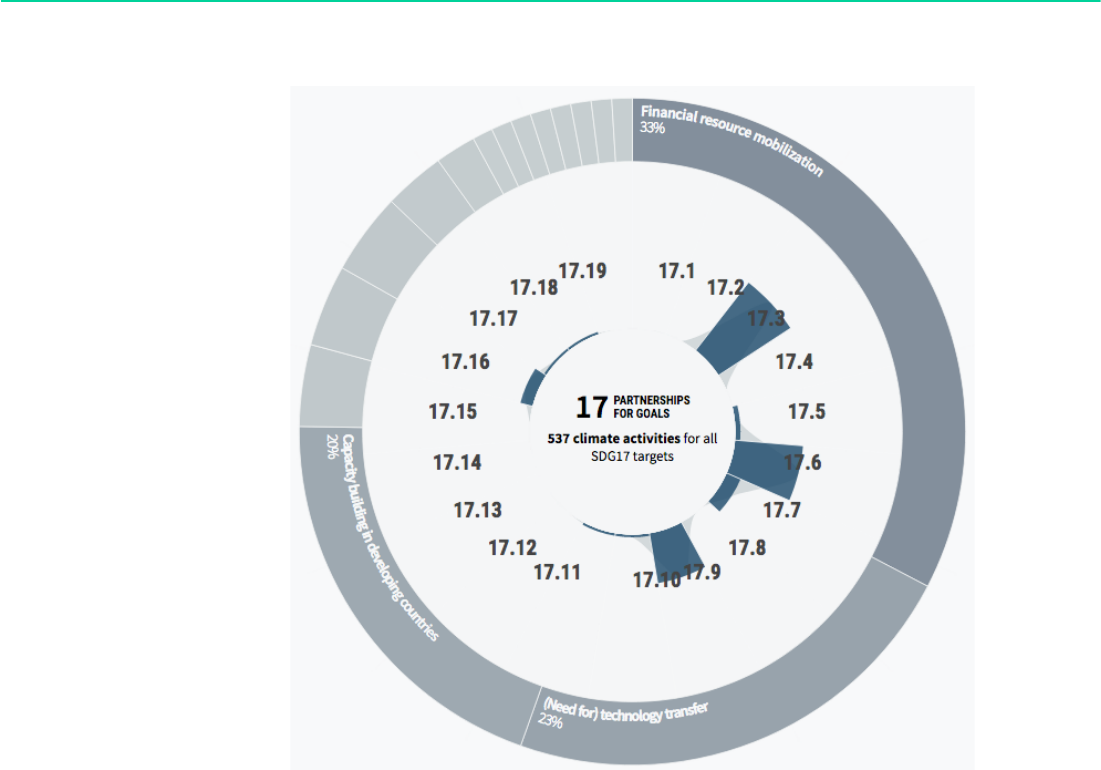

Sixth-strongest links to NDCs: partnerships for goals (SDG 17)

Addressing climate change requires financial resources, the widespread adoption of new

technologies (Iyer et al. 2018), capacity building, climate-friendly trade policies (Dröge et

al. 2016; Brandi 2017), improved policy coherence, and intensive global cooperation. SDG 17

Figure 7: Links between NDC activities and SDG 6 (clean water and sanitation)

Source: ndc-sdg.info

18 Stockholm Environment Institute

(partnerships for goals) calls for strengthening the means of implementation to reach the goals,

and in particular global partnership to work towards sustainable development. It has no fewer

than 19 targets covering a wide range of areas. These are set out in five subsections: finance,

technology, capacity building, trade and “systemic issues” (policy and institutional coherence). It

is therefore not surprising that SDG 17 is one of the most important SDGs for climate change. In

total, around 7% of NDC activities are connected to SDG 17. The most represented targets of Goal

17 are SDG 17.3 (mobilize additional financial resources for developing countries from multiple

sources), SDG 17.6 (enhanced North-South, South-South and triangular cooperation on and

access to science, technology and innovation and enhanced knowledge sharing) and SDG 17.9

(enhanced international support for capacity building in developing countries). In terms of climate

actions, most activities relate to financial resource mobilization, capacity building, research and

technology cooperation. With more than 86% of the NDCs including activities corresponding to

SDG 17, it seems clear that the relevance of international partnerships is truly global (Figure 7).

In the area of finance, SDGs 17.1–17.5 call for mobilization of resources from many sources,

including within developed countries. Developed countries have committed to mobilize US$100

billion a year in climate finance by 2020. As many developing countries condition their NDC

activities on the prospect of assistance and partnership (Pauw et al. 2016), international

development finance for climate action and sustainable development is a critical issue and key

to achieve the long-term goals of the two agendas. Moreover, one of the key objectives of the

Paris Agreement is to make all financial flows consistent with low-carbon and climate-resilient

development pathways. The need for international partnerships and financial support both for

climate mitigation and for adaptation is reflected in the type of identified NDC climate activities

Figure 8: Links between NDC activities and SDG 17 (partnerships for the goals)

Source: ndc-sdg.info

Connections between the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda 19

that are almost equally addressing each area – 21% adaptation, 29% mitigation, 41% adaptation

and mitigation concurrently.

4.2 The middle tier: SDGs with mid-level connections to NDC activities

Beyond the six SDGs with strong connections, several climate activities contribute to other SDGs,

but to a limited extent. The most prominent goal in this category is SDG 9 (industry, innovation

and infrastructure), which is seen as a crucial driver of economic growth and development.

Following is SDG 13 (climate action), with its strong focus on adaptive capacity and climate

education. In this category, there is also SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth), which aims

to increase labour productivity and reduce the unemployment rate; SDG 3 (good health and well-

being), where eorts are made to alleviate negative health impacts from climate change; SDG 14

(life below water), focusing on conservation and sustainable use of the oceans, seas and marine

resources; and lastly, SDG 4 (quality education), which places obtaining a quality education as

a foundation for achieving sustainable development. The remainder of this section presents the

pertinent findings at target and climate action levels for the respective goals, aiming to highlight

potential overlaps and gaps between climate activities and sustainable development.

Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure (SDG 9)

SDG 9 (industry, innovation and infrastructure) lies at the intersection of infrastructure, energy,

and housing. This goal calls for building resilient infrastructure, promoting inclusive and

sustainable industrialization, and fostering innovation. Sustained investment in infrastructure

and innovation are seen as crucial for economic growth as well as for low-carbon and

Figure 9: Links between NDC activities and SDG 9 (industry, innovation and infrastructure)

Source: ndc-sdg.info

20 Stockholm Environment Institute

climate-resilient development (New Climate Economy 2016). Around 7% of NDC activities

are connected to SDG 9. The majority of relevant climate actions focus on building new and

upgrading existing infrastructure. To do this, issues such as resource eiciency, promotion of

green industry, and revisiting building codes and standards are particularly important.

Under this SDG, more than half of NDC activities relate to SDG 9.4 (upgrading infrastructure,

resource eiciency and new technologies), while 25% relate to SDG 9.1 (resilient infrastructure)

(Figure 8). The implementation of the Paris Agreement to limit global warming requires

substantial investments in cleaner infrastructure (McCollum et al. 2018). On the one hand,

existing infrastructure will need to be upgraded, for instance, by improving eiciency and

reducing emissions of coal power plants, installing carbon capture and storage, but also by

improving energy eiciency in current buildings, greening public transport. On the other hand,

new infrastructure will be essential for a full transition to carbon neutrality, in particular in the

energy sector where renewable energy sources would need to replace existing fossil fuel-based

power plants, and to account for increasing energy demand.

The NDCs recognize that climate-resilient infrastructure is a key factor for decreasing socio-

economic and bio-physical vulnerability. Climate impacts such as sea-level rise, flooding and

other extreme weather events make this SDG particularly important for vulnerable countries.

While new and upgraded infrastructure will be essential for the transition to a low-carbon

economy, this is also needed to increase resilience of communities.

NDC activities in this SDG additionally interact with other sectors, such as housing and industry

(SDG 11) and energy (SDG 7). Many activities discuss new and resilient infrastructure under

the mandate of energy savings and resource eiciency. There are, however, gaps between

Figure 10: Links between NDC activities and SDG 13 (climate action)

Source: ndc-sdg.info

Connections between the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda 21

NDC activities and the full ambitions of this goal. For example, focus is lacking on the need to

strengthen both the capacities of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and ambitions in

climate- and sustainable development-related research and development.

Close to two thirds (63%) of NDC activities connected to SDG 9 contribute to climate change

mitigation, highlighting once more the large number of activities that address infrastructure

upgrades for resource eiciency, buildings codes and green industry, among others. SDG 9 also

contributes to adaptation through development of resilient infrastructure, but to a far lesser

extent. Finally, 93% of all activities are not quantified, but expressed merely in general terms.

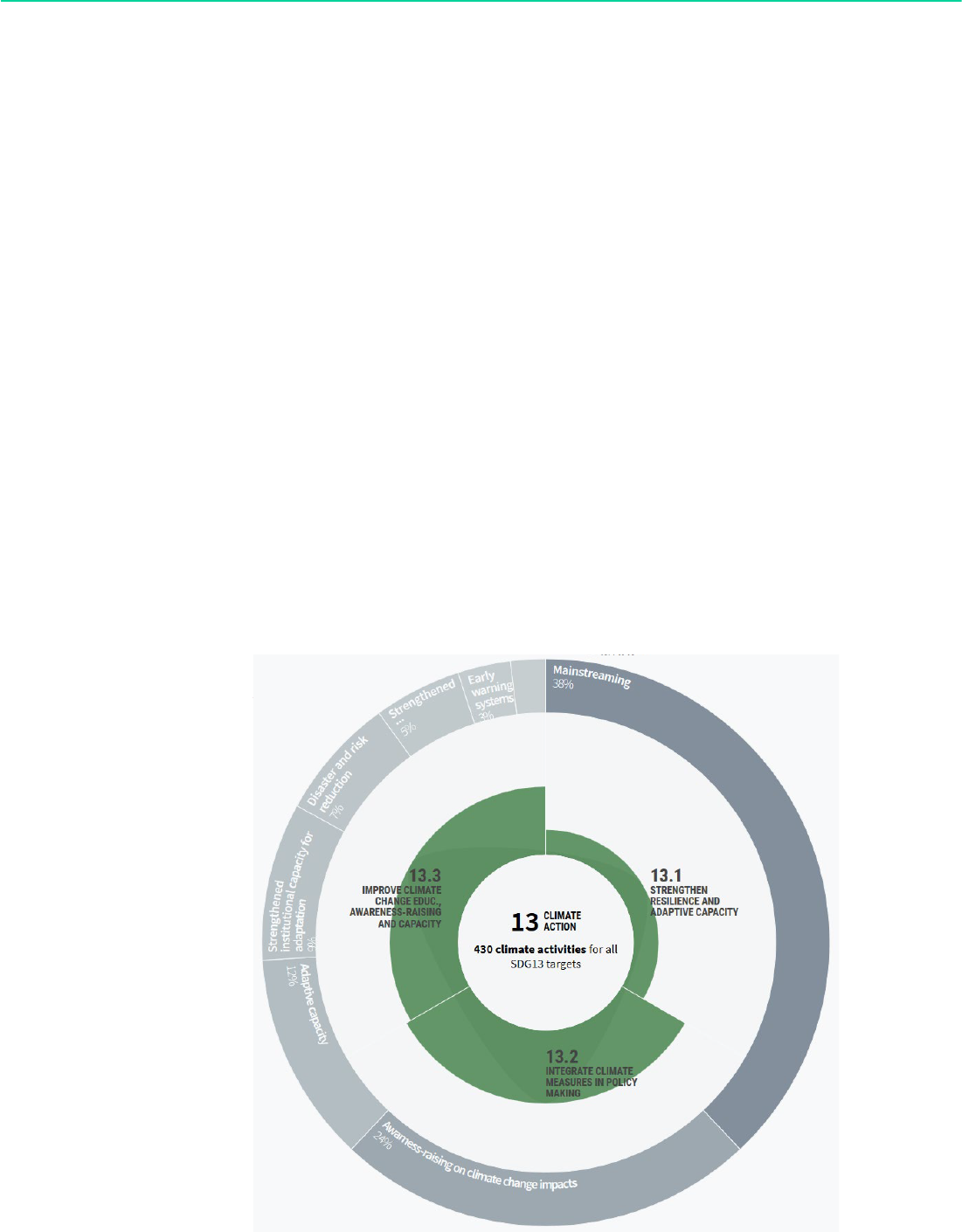

Climate Action (SDG 13)

Combating climate change is naturally present in all NDC activities. Failing to address climate

change impacts can undermine progress towards most SDGs (Le Blanc 2015). Many activities

not only declare mitigation targets but also cite the importance of adaptation. While it might

sound strange that SDG 13 climate action) is not the most prominent SDG, a key message from

NDC-SDG Connections is that NDCs go beyond SDG 13, and that climate action is a concern for

the whole spectra of sustainable development (Dzebo et al. 2017). While all NDCs are inherently

connected to climate change, only 6% of activities directly correspond to SDG 13 and its

targets. A reason for this is that the SDG targets are relatively narrow, focusing on resilience

and adaptive capacity (13.1), policy mainstreaming (13.2) and education and awareness (13.3),

which has overlaps with SDG 4.

At the level of targets, the NDC activities most frequently relate to SDG 13.2 (integrate climate

change measures into national policies, strategies and planning) and SDG 13.3 (improve

education, awareness-raising and human and institutional capacity on climate change

mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction and early warning), with a bit less focus on SDG 13.1

(strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters

in all countries). Following from the logic of the targets of SDG 13, two-thirds of the activities

relate to climate change adaptation. In terms of climate actions, countries address mainly

issues around mainstreaming climate change into national policies and strategies, increasing

awareness-raising on climate impacts, and on building adaptive capacity (Figure 9).

The 2030 Agenda reflects the centrality of climate change mitigation and adaptation for

global sustainable development. Climate change issues cut across the agenda, appearing in

targets under several other goals. SDG 13 acknowledges that the UNFCCC is the main forum

for negotiating the global climate response. It does not set specific, measurable targets for

mitigation or adaptation, leaving that task to the Paris Agreement. Many activities in SDG 13

refer to themes highly relevant for other SDGs, including energy (SDG 7) and education (SDG

4) as well as resilience and disaster risk management, which appear under several SDGs, most

notably SDG 2 (zero hunger) and SDG 11 (sustainable cities). However, NDC activities under

SDG 13 disproportionately address climate change adaptation (67%) as compared to mitigation

(9%, and 21% adaptation and mitigation concurrently). This is in part due to the aim of SDG 13

targets, which individually address adaptation (13.1), but not mitigation. Another contributor

is the finding that only 1% of climate activities attributed to SDG 13 are quantifiable. SDG 13 is

mainly about awareness raising and procedural change, and less about transformation towards

a low-carbon society.

Decent work and economic growth (SDG 8)

SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth) aims to achieve full and productive employment,

and decent work, for all women and men by 2030. Thus, the main focus areas are:

economic growth and economic development through sustained, inclusive and sustainable

growth; full and productive employment; and decent work for all. Two additional key

elements are: improving resource eiciency and decoupling economic growth from

22 Stockholm Environment Institute

environmental degradation (UNEP 2011; Schandl et al. 2016; Rockström et al. 2017; New

Climate Economy, 2018).

The SDG 8-relevant activities in countries’ NDCs focus mainly on promoting a low-carbon

economy, sustainable tourism, and unemployment reduction. In general, NDCs underscore

the significance of SDG 8, with 4% of NDC activities connecting to this SDG. The bulk of

NDC activities largely relate to just two of the 10 targets: SDG 8.4 (improve global resource

eiciency in consumption and production and endeavor to decouple economic growth from

environmental degradation) and SDG 8.1 (sustain per capita economic growth in accordance

with national circumstances). Recurrent climate actions are promoting a low-carbon economy,

sustainable tourism (also SDG 8.9) and reducing unemployment (also SDG 8.5) (Figure 10).

Limiting global warming to no more than 2°C require a fast and radical transformation of the

economy, while a temperature increase limit of 1.5°C is even more disruptive and requires global

CO2 emissions to reach net zero by 2050 at the latest, as shown by the IPCC Special Report on

Global Warming of 1.5°C (IPCC 2018).

NSDS’s could complement climate policies related to this goal by focusing on issues such as

increased access to financial services, protecting labour rights, and eradicating forced labour. Poor

communities are most vulnerable to climate change impacts due to their low capacity to adapt, and

the fact that they are more often located in disaster-prone areas. In that sense, more than two-thirds

of NDC activities related to SDG 8 focus on adaptation. However, mitigation also plays an important

role for SDG8 because it is expected to substantially transform countries’ economies and aect

labour in various sectors (Babiker and Eckaus, 2007; ILO, 2010; Fankhauser et al. 2008).

Figure 11: Links between NDC activities and SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth)

Source: ndc-sdg.info

Connections between the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda 23

Good health and well-being (SDG 3)

SDG 3 (good health and well-being) focuses on preventing disease, reducing preventable deaths,

and boosting health and well-being by improving access to health care services, promoting

healthy lifestyles, and ensuring a healthy and safe environment for all. NDC activities have great

potential to contribute directly and indirectly to this SDG, both through mitigation – for instance,

by improving air quality (Braspenning Radu et al. 2016) – and through adaptation – for instance,

by increasing resilience of communities in high-risk areas (Watts et al. 2015; Watts et al. 2017).

In that regard, many climate actions relevant to SDG 3 relate to reducing climate-induced health

risks and preventing communicable diseases (see also Wu et al. 2016). Climate change itself can

lead to increased spread of tropical diseases such as malaria. At the same time, climate change

indirectly aects health for all through deteriorating air, soil and water quality. Climate-related

extreme weather events not only directly cause deaths and injuries, but can also harm health care

services and vital infrastructure (Smith et al. 2014).

These important links are, however, poorly reflected in the NDCs as just over 3% of all NDC

activities mention health, indicating a lower priority compared with other sectors. The focus of

SDG 3-relevant climate actions is on SDG 3.3 (end epidemics and other communicable diseases),

SDG 3.9 (reduce illness and deaths from chemicals and pollution), and SDG 3.8 (provide

access to universal health care and vaccinations). Beyond these targets, climate actions are

primarily concerned with reducing climate-induced health risks, and preventing the spread of

communicable diseases (Figure 11).

Beyond these links are opportunities to work with closely linked sectors such as sanitation

(SDG6) and nutrition (SDG2), gender equality (SDG5), and reduced inequalities (SDG10) – all of

which have the potential to play important roles in dealing with health-related climate impacts.

Figure 12: Links between NDC activities and SDG 3 (good health and well-being)

Source: ndc-sdg.info

24 Stockholm Environment Institute

The link to eects on global health of these activities is not very strong; this connection should

be made clearer (Dickin and Dzebo 2018).

NDC activities related to SDG 3 mostly tackle climate change adaptation, as they focus on

provision of universal, improved and resilient health-care systems. However, as indicated

above, climate change mitigation can also play an important role in achieving SDG 3 targets

related to pollutants, particularly through a direct reduction in air pollutants through the

reduced use of fossil fuels.

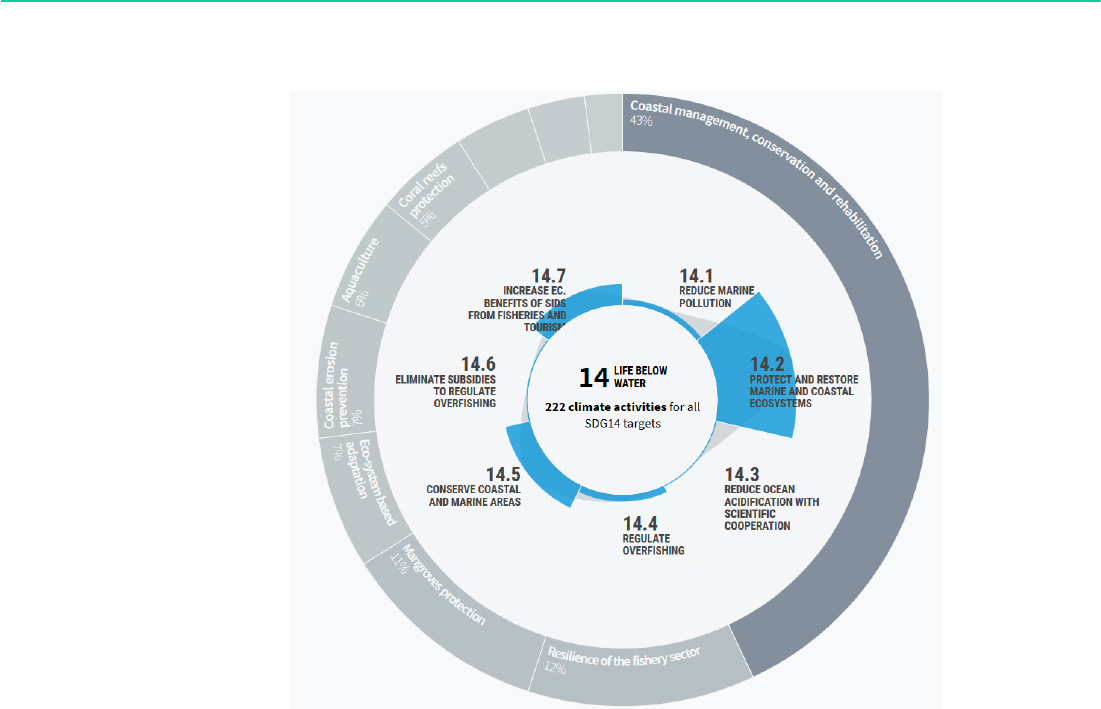

Life below water (SDG 14)

Climate change is a threat to ocean ecosystems and to coastal communities and livelihoods

that depend on marine resources. SDG 14 (life below water) focuses on conserving and

sustainably using the oceans, seas and marine resources. The oceans provide livelihoods for

a sizeable share of the world population. Many communities in developing countries depend

heavily on marine resources and fishing. Climate change is linked to the warming of the

world’s oceans. This threatens marine ecosystems and aects global weather patterns. It also

causes sea level rise, which threatens many coastal communities, including major cities, and

accelerates coastal erosion. In addition, warming seas and ocean acidification are likely to

reduce the capacity of the oceans to act as a carbon sink.

Only around 3% of NDC activities relate to SDG 14. This means that the focus on oceans is

well behind other climate-sensitive areas. As Figure 12 shows, NDC activities are primarily

concerned with coastal management and protection (in particular of mangroves), and on

increasing resilience of the fish stock. In terms of SDG targets, SDG 14.2 (protection and

restoration of marine and coastal ecosystems) is relevant to the largest share of these

Figure 13: NDC activities linked to SDG 14 (life below water)

Source: ndc-sdg.info

Connections between the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda 25

activities, followed by SDG 14.5 (conservation of coastal and marine areas) and SDG 14.7

(increasing economic benefits to small island developing states and least-developed countries

from marine resources). Pertinent issues such as marine pollution, particularly from micro-

plastics, and ocean acidification are largely excluded from NDCs. However, climate change

is an important stressor on marine and coastal ecosystems. It is associated with significant

adverse impacts, including ocean acidification and coral bleaching (Hughes et al. 2003).

Most activities (roughly 70%) related to this SDG are adaptation oriented. Furthermore, despite

its focus on life below water, achieving SDG 14 is highly dependent on terrestrial activities

and vice versa. Thus, ocean health is central to multiple SDGs (Unger et al. 2017; Neumann

and Unger 2019). Issues such as coastal protection, mangrove protection, and land use and

management have strong synergies with SDG 2 (no hunger) and SDG 15 (life on land).

In order to emphasize the lack of ocean-related climate action, in 2017 the UN organized an

Ocean Conference, focused particularly on Small Island Developing States. The aim was to

raise the profile of the many threats that are aecting the world’s oceans and, in turn, people’s

lives. Among the issues addressed were: climate change, land-based pollution, coral bleaching,

overfishing, marine habitat degradation, ocean acidification, and the importance of healthy

oceans to sustainable development and the achievement of the SDGs.

Figure 14: NDC activities linked to SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production)

Source: ndc-sdg.info

26 Stockholm Environment Institute

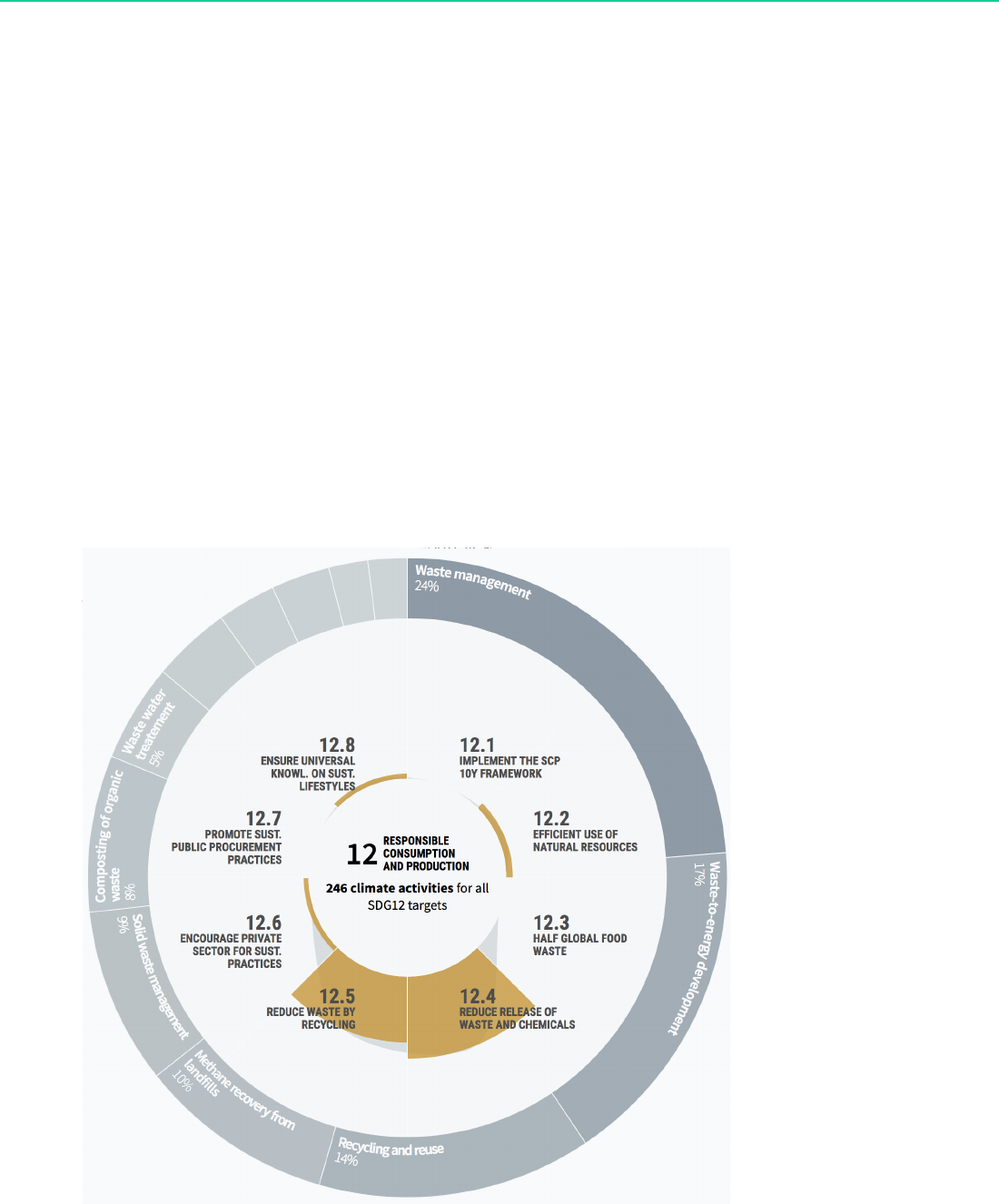

Responsible consumption and production (SDG 12)

SDG 12 intends to “ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns”. Overall,

the production of goods and services today not only depletes resources (water, energy,

rare earths, wood, etc.) and causes environmental degradation (water and air pollution,

waste), but also generates huge amounts of greenhouse gases (Garnett, 2011; Arto and

Dietzenbacher, 2014). The goods and services consumed contribute to climate change

throughout their whole lifecycle – from extraction of raw materials, production and

transportation, to use and end of life (Gardner et al. 2018; Godar et al. 2016). Rethinking and

redesigning production systems, changing consumption habits (reducing consumption, and

by consuming goods with lower environmental footprints) (e.g. Hedenus et al. 2014), and

establishing more circular resource management (Lieder and Rashid 2016) are key to fighting

climate change.

Around 3% of NDC activities are connected to SDG 12, while 62 % of the NDCs include SDG

12-related activities. The majority of climate actions relate to improving waste management,

using waste as a source of energy, recycling and reuse; and recovering methane from

landfills. Two SDG targets are most relevant for SDG12-related NDC activities: SDG 12.4

(environmentally sound management of chemicals and all wastes throughout their lifecycle)

and SDG 12.5 (reducing waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and

reuse). Most activities in the NDCs, thus, focus on recycling and reducing waste. Conversely,

the production side receives little attention. This represents a gap, given that the sustainable

production of goods and services is essential and strongly linked to emissions and other

types of pollution, and to the use of inputs such natural resources and raw materials

(Müller et al. 2015b). The focus on waste and waste-to-energy indicates strong synergies

Figure 15: NDC activities linked to SDG 4 (quality education)

Source: ndc-sdg.info

Connections between the Paris Agreement and the 2030 Agenda 27

between SDG 12 and SDG 7. However, countries’ NDCs also mention agriculture and water

as being important for sustainable consumption and production. In addition, there are

strong links with cities and urbanization, arguably because waste management in urban

areas is often a challenge.

Given the high potential of sustainable consumption and production to reduce GHG emissions,

it is no surprise that almost all NDC activities related to SDG12 that can be clearly categorized

refer to climate change mitigation. However, sustainable approaches, for instance, in agricultural

production, could increase the resilience of soil quality in the face of climate change, and could

also reduce the use of valuable resources, such as water.

Quality education (SDG 4)

Several countries’ NDCs feature activities corresponding to SDG 4 (quality education), which calls

for inclusive and equitable quality education, and the promoting lifelong learning opportunities

for all. Education ensures the next generation´s awareness of climate change, and encourages

the adoption of more climate-friendly lifestyles. However, not more than 3% of all NDC activities

incorporate actions relating to systemic changes in awareness and education.

Climate actions in SDG 4 predominantly focus on awareness raising and provision of vocational

training. The need to strengthen climate change research, and to incorporate climate change

into educational curricula and programmes receive mention, but not to a great degree. Countries

emphasize the need for education and awareness both on the need for general reduction of

greenhouse gas emissions, but also, and particularly, on the need for climate change adaptation,

for example, through community-based education and awareness-raising activities.

With regards to the SDG targets, almost exclusively all activities correspond to SDG 4.7 (ensure

knowledge and skills to promote sustainable development) (Figure 13). Furthermore, from a

climate perspective, SDG 4 overlaps very much with SDG 13 (climate action) through SDG 13.3

(improve education, awareness-raising and human and institutional capacity on climate change

mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction and early warning). Hence, more climate activities

come under SDG 13.3 than under SDG 4. NDC activities related to SDG 4 almost entirely address

climate change adaptation (82%). However, life-style changes; community-based climate action,

education and awareness raising; and community-level capacity building that targets greenhouse

gas emissions reductions hold high potential for climate change mitigation. Thus, these actions

should play a more important in countries’ strategies than they currently do.

4.3 The bottom tier: SDGs with few connections to NDC activities

Some SDGs within the 2030 Agenda focus mainly on the social and political issues. Among these

are: SDG 1 (no poverty), SDG 5 (gender equality), SDG 10 (reduced inequalities) and SDG 16

(peace, justice and strong institutions). These SDGs are far less connected with NDC activities.

Nevertheless, important connections between these SDGs and climate change should not be

overlooked (Klinsky et al. 2017). This section discusses those NDCs that included activities

relating to these goals.

First, only 71 countries and 2% of total NDC activities address SDG 1 (no poverty). These activities

focus on reducing relative poverty and increasing resilience of vulnerable communities. Climate

plans hardly commit to access to basic services (SDG 1.4) or social protection schemes (SDG

1.3). Yet, climate change can strongly aect vulnerable communities, which can fall further

into poverty as the result of related changes (IPCC 2014). Access to basic services is essential

for increased resilience and adaptation to potential environmental changes. Moreover, social

protection schemes can help those aected to recover more quickly (Burke et al. 2015). In

addition, climate change mitigation measures themselves can impact the poor, for example,

by leading to increased prices through energy or carbon taxes, or through the use of more

28 Stockholm Environment Institute

expensive technologies for electricity production (Hirth and Ueckerdt, 2013; Jakob and Steckel,

2016; Labandeira et al. 2009). Policymakers should take such impacts into account, and

consider complementary measures that protect poor households from such adverse eects.

All themes where access to services and social protection are the vision of an SDG or a target

are left to NSDS’s.

Second, 56 countries included at least one activity related to SDG 5 (gender equality) in their

NDCs. Most of these activities focus on integrating gender considerations into national policy

design, and on increasing protection of women from climate change risk, given that women

are particularly vulnerable to climate impacts (Djoudi et al. 2016). With regards to SDG targets,

most activities relate to SDG 5.5 (ensure women’s full and eective participation and equal

opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision-making in political, economic and public life).

Many women lack access to knowledge, resources, capital, and decision-making power, which

makes them more vulnerable to climate change impacts. In particular, SDG 5.5 calls for increasing

women’s full and eective participation and equal opportunities for leadership. There is currently

an underrepresentation of women in climate change negotiations and decision-making at all

levels (Sellers 2016).

Third, only 23 countries’ NDCs included activities that relate to SDG 10 “reducing inequality”.

However, evidence suggests that climate change hurts both poor countries the most, and the

poorest within countries the most (Sovacool et al. 2017). Poor and vulnerable communities are

subject to double exposure; climate change and (economic) globalization that is not inclusive

(O’Brien and Leichenko 2000). Thus, reducing climate risks can also help address poverty.

The majority of climate actions in NDC activities are focusing on inequality reduction, and the

inclusion of low-income and vulnerable communities.

Lastly, SDG 16 (peace, justice and strong institutions) has fewest connections to NDC activities.

Just a dozen of countries’ NDCs call for eective and accountable institutions and to integrate

climate change impacts in security measures. For example, fuelwood scarcity has been linked

to violence against women (Patrick 2007). Furthermore, SDG 16 aims to promote rule of law,

strong institutions and participation of all to foster sustainable development. These aspects are

a precondition to achieve a multiple SDGs as well as a cross-cutting theme that runs through the

entire 2030 Agenda (Tosun and Leininger 2017).

5. Discussion

5.1 NDCs are more than climate action plans

In light of the multiple overlaps, the assessed NDCs can be regarded not only as climate plans

but also as de facto sustainable development plans because they include many priorities that

reflect the 2030 Agenda. NDCs were initially intended to indicate countries’ ambitions to reduce

emissions of greenhouse gases. However, as this was a bottom-up driven process, countries

chose to include other priorities beyond mitigation targets (Brandi et al. 2017). The connections

between NDCs and SDGs indicate that the process of coordinating the Paris Agreement and

the 2030 Agenda does not start from zero in these countries but will build on existing potential.

However, while our analysis finds connections between climate activities in countries’ NDCs

and the 17 SDGs as described above, gaps remain. The presence of these gaps underscores the

untapped potential for further alignment of the two agendas. This section highlights the potential

for complementarity with the NSDS’s and identifies gaps where ambitions of the next NDC cycle

could be scaled-up.

As shown in Section 4 climate action overlaps with all 17 goals to various extents, with energy

(SDG7) being the most prominent climate action, followed by land use (SDG14), agriculture