CDC’s Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain is intended to improve communication between providers and

patients about the risks and benefits of opioid therapy for chronic pain, improve the safety and effectiveness of pain

treatment, and reduce the risks associated with long-term opioid therapy, including opioid use disorder and overdose.

The Guideline is not intended for patients who are in active cancer treatment, palliative care, or end-of-life care.

Nonpharmacologic therapy and nonopioid pharmacologic therapy

are preferred for chronic pain. Clinicians should consider opioid

therapy only if expected benefits for both pain and function are

anticipated to outweigh risks to the patient. If opioids are used,

they should be combined with nonpharmacologic therapy and

nonopioid pharmacologic therapy, as appropriate.

Before starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, clinicians

should establish treatment goals with all patients, including

realistic goals for pain and function, and should consider how

opioid therapy will be discontinued if benefits do not outweigh

risks. Clinicians should continue opioid therapy only if there is

clinically meaningful improvement in pain and function that

outweighs risks to patient safety.

Before starting and periodically during opioid therapy, clinicians

should discuss with patients known risks and realistic benefits

of opioid therapy and patient and clinician responsibilities for

managing therapy.

DETERMINING WHEN TO INITIATE OR CONTINUE OPIOIDS FOR CHRONIC PAIN

1

2

3

CLINICAL REMINDERS

•

Opioids are not first-line or routine

therapy for chronic pain

•

Establish and measure goals for pain

and function

•

Discuss benefits and risks and

availability of nonopioid therapies with

patient

IMPROVING PRACTICE THROUGH RECOMMENDATIONS

LEARN MORE | www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html

GUIDELINE FOR PRESCRIBING

OPIOIDS FOR CHRONIC PAIN

When starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, clinicians should prescribe

immediate-release opioids instead of extended-release/long-acting (ER/LA)

opioids.

When opioids are started, clinicians should prescribe the lowest effective dosage.

Clinicians should use caution when prescribing opioids at any dosage, should

carefully reassess evidence of individual benefits and risks when considering

increasing dosage to ≥50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME)/day, and should

avoid increasing dosage to ≥90 MME/day or carefully justify a decision to titrate

dosage to ≥90 MME/day.

Long-term opioid use often begins with treatment of acute pain. When opioids

are used for acute pain, clinicians should prescribe the lowest effective dose of

immediate-release opioids and should prescribe no greater quantity than needed

for the expected duration of pain severe enough to require opioids. Three days or

less will often be sufficient; more than seven days will rarely be needed.

Clinicians should evaluate benefits and harms with patients within 1 to 4 weeks

of starting opioid therapy for chronic pain or of dose escalation. Clinicians

should evaluate benefits and harms of continued therapy with patients every 3

months or more frequently. If benefits do not outweigh harms of continued opioid

therapy, clinicians should optimize other therapies and work with patients to

taper opioids to lower dosages or to taper and discontinue opioids.

OPIOID SELECTION, DOSAGE, DURATION, FOLLOW-UP, AND DISCONTINUATION

4

5

6

8

9

10

11

12

7

ASSESSING RISK AND ADDRESSING HARMS OF OPIOID USE

Before starting and periodically during continuation of opioid therapy, clinicians

should evaluate risk factors for opioid-related harms. Clinicians should

incorporate into the management plan strategies to mitigate risk, including

considering offering naloxone when factors that increase risk for opioid overdose,

such as history of overdose, history of substance use disorder, higher opioid

dosages (≥50 MME/day), or concurrent benzodiazepine use, are present.

Clinicians should review the patient’s history of controlled substance prescriptions

using state prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) data to determine

whether the patient is receiving opioid dosages or dangerous combinations that

put him or her at high risk for overdose. Clinicians should review PDMP data when

starting opioid therapy for chronic pain and periodically during opioid therapy for

chronic pain, ranging from every prescription to every 3 months.

When prescribing opioids for chronic pain, clinicians should use urine drug testing

before starting opioid therapy and consider urine drug testing at least annually to

assess for prescribed medications as well as other controlled prescription drugs and

illicit drugs.

Clinicians should avoid prescribing opioid pain medication and benzodiazepines

concurrently whenever possible.

Clinicians should offer or arrange evidence-based treatment (usually medication-

assisted treatment with buprenorphine or methadone in combination with

behavioral therapies) for patients with opioid use disorder.

CLINICAL REMINDERS

•

Use immediate-release opioids

when starting

•

Start low and go slow

•

When opioids are needed for

acute pain, prescribe no more

than needed

•

Do not prescribe ER/LA opioids

for acute pain

•

Follow-up and re-evaluate risk

of harm; reduce dose or taper

and discontinue if needed

CLINICAL REMINDERS

•

Evaluate risk factors for

opioid-related harms

•

Check PDMP for high dosages

and prescriptions from other

providers

•

Use urine drug testing to identify

prescribed substances and

undisclosed use

•

Avoid concurrent benzodiazepine

and opioid prescribing

•

Arrange treatment for opioid use

disorder if needed

LEARN MORE | www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html

LEARN MORE | www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html

ASSESSING BENEFITS AND

HARMS OF OPIOID THERAPY

THE EPIDEMIC

The United States is in the midst

of an epidemic of prescription

opioid overdose deaths, which

killed more than 14,000 people in

2014 alone.

Since 1999, sales of prescription

opioids—and related overdose

deaths—have quadrupled.

GUIDANCE FOR OPIOID PRESCRIBING

The CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain

1

provides up-to-date guidance on prescribing and weighing

the risks and benefits of opioids.

• Before starting and periodically during opioid therapy, discuss

the known risks and realistic benefits of opioids.

• Also discuss provider and patient responsibilities for

managing therapy.

• Within 1-4 weeks of starting opioid therapy, and at least every 3

months, evaluate benefits and harms with the patient.

ASSESS BENEFITS OF OPIOID THERAPY

Assess your patient’s pain and function regularly. A 30%

improvement in pain and function is considered clinically

meaningful. Discuss patient-centered goals and improvements

in function (such as returning to work and recreational

activities) and assess pain using validated instruments such

as the 3-item (PEG) Assessment Scale:

1. What number best describes your pain on average in the past

week? (from 0=no pain to 10=pain as bad as you can imagine)

2. What number best describes how, during the past week, pain

has interfered with your enjoyment of life? (from 0=does not

interfere to 10=completely interferes)

3. What number best describes how, during the past week, pain

has interfered with your general activity? (from 0=does not

interfere to 10=completely interferes)

If your patient does not have a 30% improvement in pain and function,

consider reducing dose or tapering and discontinuing opioids.

Continue opioids only as a careful decision by you and your patient

when improvements in both pain and function outweigh the harms.

165,000

Since 1999, there

have been more than

deaths from overdose related to

prescription opioids.

1

Recommendations do not apply to pain management in the context of active cancer treatment, palliative care, and end-of-life care.

ASSESS HARMS OF OPIOID THERAPY

Long-term opioid therapy can cause harms ranging in severity from constipation and nausea to opioid use

disorder and overdose death. Certain factors can increase these risks, and it is important to assess and follow-

up regularly to reduce potential harms.

ASSESS. Evaluate for factors that could increase your

patient’s risk for harm from opioid therapy such as:

1

•

Personal or family history of substance use disorder

•

Anxiety or depression

•

Pregnancy

•

Age 65 or older

•

COPD or other underlying respiratory conditions

•

Renal or hepatic insufficiency

2

CHECK. Consider urine drug testing for other

prescription or illicit drugs and check your state’s

prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) for:

•

Possible drug interactions (such as

benzodiazepines)

•

High opioid dosage (≥50 MME/day)

•

Obtaining opioids from multiple providers

3

4

DISCUSS. Ask your patient about concerns and determine

any harms they may be experiencing such as:

•

Nausea or constipation

•

Feeling sedated or confused

•

Breathing interruptions during sleep

•

Taking or craving more opioids than prescribed or

difficulty controlling use

OBSERVE. Look for early warning signs for overdose

risk such as:

•

Confusion

•

Sedation

•

Slurred speech

•

Abnormal gait

If harms outweigh any experienced benefits, work with your patient to reduce dose, or taper and discontinue opioids and

optimize nonopioid approaches to pain management.

TAPERING AND DISCONTINUING OPIOID THERAPY

Symptoms of opioid withdrawal may include drug craving, anxiety, insomnia, abdominal pain, vomiting,

diarrhea, and tremors. Tapering plans should be individualized. However, in general:

Go Slow

1

Consult

2

To minimize symptoms of opioid

withdrawal, decrease 10% of the original

dose per week. Some patients who have

taken opioids for a long time might find

slower tapers easier (e.g., 10% of the

original dosage per month).

Support

3

During the taper, ensure patients

receive psychosocial support for

anxiety. If needed, work with mental

health providers and offer or arrange

for treatment of opioid use disorder.

Work with appropriate specialists

as needed—especially for those at

risk of harm from withdrawal such

as pregnant patients and those with

opioid use disorder.

Improving the way opioids are prescribed can ensure patients have access to safer, more effective chronic pain treatment

while reducing the number of people who misuse, abuse, or overdose from these drugs.

LEARN MORE | www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html

Dosages at or above

50 MME/day

increase risks for overdose by at least

the risk at

<20

MME/day.

2x

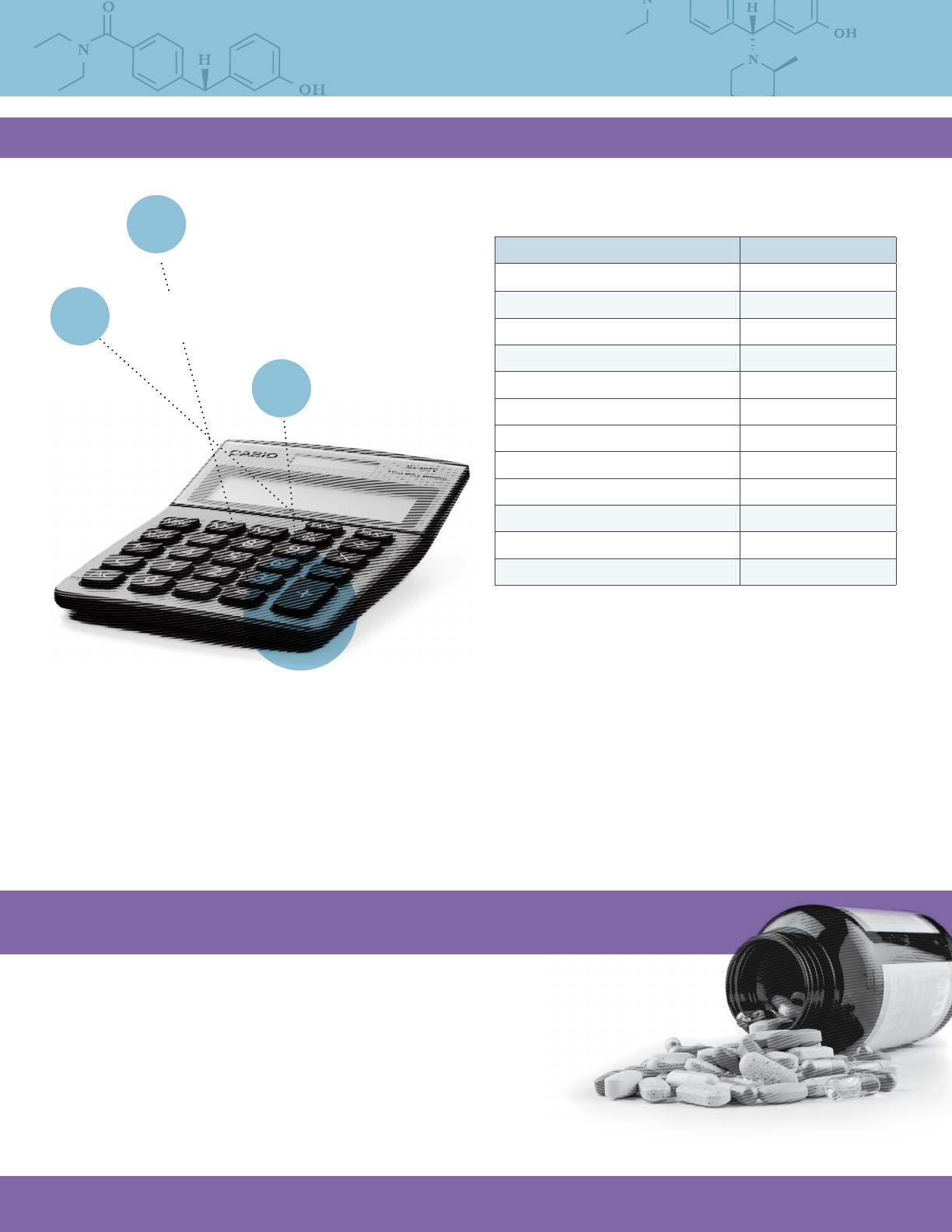

CALCULATING TOTAL DAILY DOSE

OF OPIOIDS FOR SAFER DOSAGE

Patients prescribed higher opioid dosages are at higher

risk of overdose death.

In a national sample of Veterans Health Administration (VHA)

patients with chronic pain receiving opioids from 2004–2009,

patients who died of opioid overdose were prescribed an average

of 98 MME/day, while other patients were prescribed an average

of 48 MME/day.

Calculating the total daily dose of opioids helps identify

patients who may benefit from closer monitoring, reduction or

tapering of opioids, prescribing of naloxone, or other measures

to reduce risk of overdose.

50 MME/day: 90 MME/day:

• 50 mg of hydrocodone (10 tablets of hydrocodone/ • 90 mg of hydrocodone (9 tablets of hydrocodone/

acetaminophen 5/300) acetaminophen 10/325)

• 33 mg of oxycodone (~2 tablets of oxycodone • 60 mg of oxycodone 12 tablets of hydrocodone/

sustained-release 15 mg) acetaminophen 7.5/300)

• 12 mg of methadone ( <3 tablets of methadone 5 mg) • ~20 mg of methadone (4 tablets of methadone 5 mg)

Higher Dosage, Higher Risk.

Higher dosages of opioids are associated with higher risk of overdose and death—even relatively

low dosages (20-50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day) increase risk. Higher dosages

haven’t been shown to reduce pain over the long term. One randomized trial found no difference

in pain or function between a more liberal opioid dose escalation strategy (with average final

dosage 52 MME) and maintenance of current dosage (average final dosage 40 MME).

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO CALCULATE

THE TOTAL DAILY DOSAGE OF OPIOIDS?

HOW MUCH IS 50 OR 90 MME/DAY FOR COMMONLY PRESCRIBED OPIOIDS?

LEARN MORE | www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html

HOW SHOULD THE TOTAL DAILY DOSE OF OPIOIDS BE CALCULATED?

1

Calculating morphine milligram equivalents (MME)

DETERMINE the total daily amount

of each opioid the patient takes.

OPIOID (doses in mg/day except where noted)

CONVERSION FACTOR

Codeine 0.15

Fentanyl transdermal (in mcg/hr) 2.4

Hydrocodone 1

Hydromorphone 4

Methadone

1-20 mg/day 4

21-40 mg/day 8

41-60 mg/day 10

≥ 61-80 mg/day 12

Morphine 1

Oxycodone 1.5

Oxymorphone 3

These dose conversions are estimated and cannot account for

all individual differences in genetics and pharmacokinetics.

ADD them together.

3

2

CONVERT each to MMEs—multiply the dose for

each opioid by the conversion factor. (see table)

CAUTION:

• Do not use the calculated dose in MMEs to determine

dosage for converting one opioid to another—the new

opioid should be lower to avoid unintentional overdose

caused by incomplete cross-tolerance and individual

differences in opioid pharmacokinetics. Consult the

medication label.

USE EXTRA CAUTION:

• Methadone: the conversion factor increases at

higher doses

• Fentanyl:

dosed in mcg/hr instead of mg/day, and

absorption is affected by heat and other factors

HOW SHOULD PROVIDERS USE THE TOTAL

DAILY OPIOID DOSE IN CLINICAL PRACTICE?

• Use caution when prescribing opioids at any dosage and prescribe the lowest effective dose.

• Use extra precautions when increasing to

≥

50 MME per day such as:

- Monitor and assess pain and function more frequently.

- Discuss reducing dose or tapering and discontinuing opioids

if benefits do not outweigh harms.

- Consider offering naloxone.

• Avoid or carefully justify increasing dosage to ≥90 MME/day.

LEARN MORE | www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html

CS263451

March 14, 2016

NONOPIOID TREATMENTS

FOR CHRONIC PAIN

PRINCIPLES OF CHRONIC PAIN TREATMENT

Patients with pain should receive treatment that provides the greatest benefit. Opioids are not the first-line therapy for

chronic pain outside of active cancer treatment, palliative care, and end-of-life care. Evidence suggests that nonopioid

treatments, including nonopioid medications and nonpharmacological therapies can provide relief to those suffering

from chronic pain, and are safer. Effective approaches to chronic pain should:

Use nonopioid therapies to the extent possible

Identify and address co-existing mental health

conditions (e.g., depression, anxiety, PTSD)

Focus on functional goals and improvement, engaging

patients actively in their pain management

Use disease-specific treatments when available (e.g.,

triptans for migraines, gabapentin/pregabalin/duloxetine

for neuropathic pain)

Use first-line medication options preferentially

Consider interventional therapies (e.g.,

corticosteroid injections) in patients who fail

standard non-invasive therapies

Use multimodal approaches, including

interdisciplinary rehabilitation for patients who have

failed standard treatments, have severe functional

deficits, or psychosocial risk factors

NONOPIOID MEDICATIONS

Medication

Magnitude

of benefits

Harms Comments

Acetaminophen Small

Hepatotoxic, particularly at

higher doses

First-line analgesic, probably less effective than NSAIDs

NSAIDs Small-moderate Cardiac, GI, renal First-line analgesic, COX-2 selective NSAIDs less GI toxicity

Gabapentin/pregabalin Small-moderate Sedation, dizziness, ataxia

First-line agent for neuropathic pain; pregabalin approved for fibromyalgia

Tricyclic antidepressants and

serotonin/norephinephrine

reuptake inhibitors

Small-moderate

TCAs have anticholinergic

and cardiac toxicities;

SNRIs safer and better

tolerated

First-line for neuropathic pain; TCAs and SNRIs for fibromyalgia, TCAs for

headaches

Topical agents (lidocaine,

capsaicin, NSAIDs)

Small-moderate

Capsaicin initial flare/

burning, irritation of

mucus membranes

Consider as alternative first-line, thought to be safer than systemic

medications. Lidocaine for neuropathic pain, topical NSAIDs for localized

osteoarthritis, topical capsaicin for musculoskeletal and neuropathic pain

LEARN MORE | www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html

RECOMMENDED TREATMENTS FOR

COMMON CHRONIC PAIN CONDITIONS

LEARN MORE | www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html

Low back pain

Self-care and education in all patients; advise

patients to remain active and limit bedrest

Nonpharmacological treatments: Exercise, cognitive

behavioral therapy, interdisciplinary rehabilitation

Medications

• First line: acetaminophen, non-steroidal anti inflammatory

drugs (NSAIDs)

•

Second line: Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

(SNRIs)/tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)

Migraine

Preventive treatments

• Beta-blockers

• TCAs

• Antiseizure medications

• Calcium channel blockers

• Non-pharmacological treatments (Cognitive behavioral

therapy, relaxation, biofeedback, exercise therapy)

• Avoid migraine triggers

Acute treatments

• Aspirin, acetaminophen, NSAIDs (may be combined with

caffeine)

• Antinausea medication

• Triptans-migraine-specific

Neuropathic pain

Medications: TCAs, SNRIs, gabapentin/pregabalin,

topical lidocaine

Osteoarthritis

Nonpharmacological treatments: Exercise, weight

loss, patient education

Medications

• First line: Acetamionphen, oral NSAIDs, topical NSAIDs

• Second line: Intra-articular hyaluronic acid, capsaicin

(limited number of intra-articular glucocorticoid injections if

acetaminophen and NSAIDs insufficient)

Fibromyalgia

Patient education: Address diagnosis, treatment,

and the patient’s role in treatment

Nonpharmacological treatments: Low-impact

aerobic exercise (i.e. brisk walking, swimming, water

aerobics, or bicycling), cognitive behavioral therapy,

biofeedback, interdisciplinary rehabilitation

Medications

• FDA-approved: Pregabalin, duloxetine, milnacipran

• Other options: TCAs, gabapentin

Checklist for prescribing opioids for chronic pain

For primary care providers treating adults (18

+

) with chronic pain ≥ 3 months, excluding cancer, palliative, and end-of-life care

CHECKLIST

When CONSIDERING long-term opioid therapy

Set realistic goals for pain and function based on diagnosis

(eg, walk around the block).

Check that non-opioid therapies tried and optimized.

Discuss benets and risks (eg,addiction, overdose) with patient.

Evaluate risk of harm or misuse.

•

Discuss risk factors with patient.

•

Check prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) data.

•

Check urine drug screen.

Set criteria for stopping or continuing opioids.

Assess baseline pain and function (eg, PEG scale).

Schedule initial reassessment within 1

–

4 weeks.

Prescribe short-acting opioids using lowest dosage on product labeling;

match duration to scheduled reassessment.

If RENEWING without patient visit

Check that return visit is scheduled ≤ 3months from last visit.

When REASSESSING at return visit

Continue opioids only after conrming clinically meaningful improvements

in pain and function without signicant risks or harm.

Assess pain and function (eg, PEG); compare results to baseline.

Evaluate risk of harm or misuse:

•

Observe patient for signs of over-sedation or overdose risk.

– If yes: Taper dose.

•

Check PDMP.

•

Check for opioid use disorder if indicated (eg, difculty controlling use).

– If yes: Refer for treatment.

Check that non-opioid therapies optimized.

Determine whether to continue, adjust, taper, or stop opioids.

Calculate opioid dosage morphine milligram equivalent (MME).

•

If ≥ 50 MME /day total (≥ 50 mg hydrocodone; ≥ 33 mgoxycodone),

increase frequency of follow-up; consider offering naloxone.

•

Avoid ≥ 90 MME /day total (≥ 90 mg hydrocodone; ≥ 60 mg oxycodone),

or carefully justify; consider specialist referral.

Schedule reassessment at regular intervals (≤ 3months).

REFERENCE

EVIDENCE ABOUT OPIOID THERAPY

• Benets of long-term opioid therapy for chronic

pain not well supported by evidence.

• Short-term benets small to moderate for pain;

inconsistent for function.

• Insufcient evidence for long-term benets in

low back pain, headache, and bromyalgia.

NON-OPIOID THERAPIES

Use alone or combined with opioids, as indicated:

•

Non-opioid medications (eg,NSAIDs, TCAs,

SNRIs, anti-convulsants).

•

Physical treatments (eg,exercise therapy,

weight loss).

•

Behavioral treatment (eg,CBT).

•

Procedures (eg,intra-articular corticosteroids).

EVALUATING RISK OF HARM OR MISUSE

Known risk factors include:

•

Illegal drug use; prescription drug use for

nonmedical reasons.

•

History of substance use disorder or overdose.

•

Mental health conditions (eg, depression, anxiety).

•

Sleep-disordered breathing.

•

Concurrent benzodiazepine use.

Urine drug testing: Check to conrm presence

of prescribed substances and for undisclosed

prescription drug or illicit substance use.

Prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP):

Check for opioids or benzodiazepines from

other sources.

ASSESSING PAIN & FUNCTION USING PEG SCALE

PEG score = average 3 individual question scores

(30% improvement from baseline is clinically meaningful)

Q1: What number from 0

–

10 best describes

your pain in the past week?

0 = “no pain”, 10 = “worst you can imagine”

Q2: What number from 0

–

10 describes how,

during the past week, pain has interfered

with your enjoyment of life?

0 = “not at all”, 10 = “complete interference”

Q3: What number from 0

–

10 describes how,

during the past week, pain has interfered

with your general activity?

0 = “not at all”, 10 = “complete interference”

TO

LEARN MORE

www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html

U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services

Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention

March 2016