28 Social Studies and the Young Learner

I Do, We Do, You Do: Teaching

Map Skills in Early Grades

Michelle Bauml

“Here’s our state!” Courtney, a rst-grade student attending

a university laboratory school for students with mild learning

disabilities in Texas, eagerly identies a familiar place on a

simple United States desk map she is exploring. Courtney’s

student teacher

1

has prepared an explicit lesson plan for a

map skills unit focusing on the geographic theme of loca-

tion according to the state’s social studies standards. Today,

Courtney and her classmates will work with various maps to

practice using cardinal directions, which were introduced in

a previous lesson.

Student identies Texas on a desk map.

e purpose of this article is to explore the importance

of teaching map skills to children in Kindergarten–Grade

2 (K–2) and to describe key tenets of explicit instruction

as one approach to doing so. Explicit lessons that use an

I do, we do, you do scaolded approach to instruction are

eective for teaching children with or without learning dis-

abilities. Classroom teachers who are familiar with explicit

instruction may frequently use the model for reading and

math instruction while overlooking its potential for teaching

geography skills. e benets of using explicit instruction

to teach map skills include setting students up for success

with ample opportunities to practice and supporting growth

in spatial thinking.

Why Teach Map Skills?

It may seem obvious that the ability to read, use, and inter-

pret maps is a fundamental life skill in the world today.

Consider various experiences in unfamiliar places (e.g.,

oce buildings, mass transit, hiking trails) where locating

your position relative to where you are headed depends on

a map. Even global positioning systems (GPS) that provide

step-by-step directions to specic addresses require users to

apply geographic reasoning. Children need to learn about

maps, what they are for, what they represent, and how to

create and use them.

K–2 students can be taught to use and create simple maps

of familiar places.

2

ese kinds of activities not only develop

children’s condence with and understanding of geography;

they also promote a special type of thinking called spatial

thinking. Spatial thinking has three main components: “con-

cepts of space, tools of representation, and processes of rea-

soning. It is the concept of space that makes spatial thinking

a distinctive form of thinking.”

3

For example, you use spatial

thinking to locate items in your kitchen, follow a diagram to

assemble an object with multiple parts, and recognize that

some students are taller than others. Research has shown

that spatial thinking is associated with academic success,

learning, remembering, and problem-solving.

4

Spatial thinking is necessary for children to understand

that maps use symbols to represent locations of people,

places, and objects. is type of thinking is developmental.

5

e ability to think about locations, characteristics of dier

-

ent places, and relationships among those places begins to

develop in infancy as very young children become familiar

with their surroundings. Spatial thinking grows over time

and with practice.

6

Preschoolers who build with blocks and

assemble puzzles are learning spatial skills that can later be

applied to map-making.

Geographic knowledge in spatial terms—the “where-

ness” of places—is foundational to developing the kinds

of geographic thinking and reasoning that are needed to

understand the world and its interconnectedness.

7

erefore,

K–2 students need ample opportunities to practice spatial

thinking. Geography professor Sara Bednarz recommends

that spatial thinking “should not be considered an add-on to

an already full curriculum, but rather a necessary foundation

to building intellectual capacity in all learners.”

8

Social Studies and the Young Learner 36 (2) pp. 28–32

©2023 National Council for the Social Studies

November/December 2023 29

For children in grades K–2, strengthening spatial thinking

by creating and using maps to identify and examine loca-

tions, patterns, and places in the world is associated with

Dimension 2, Applying Disciplinary Concepts and Tools,

of the College, Career, and Civic Live (C3) Framework for

geography. Additionally, map skills are directly connected

to NCSS themes of PEOPLE, PLACES, AND ENVIRONMENTS and

GLOBAL CONNECTIONS, as well as the National Geography

Standards.

9

Maps can be instrumental in helping children contextual-

ize where historical, cultural, and current events have taken

place; many interdisciplinary connections can be made by

teaching about, with, and through maps.

10

For example,

a rst-grade inquiry titled “Family” published on the C3

Teachers website asks the compelling question, “How can

families be the same and dierent?”

11

e inquiry’s three

supporting questions focus on what families look like, what

families do, and what families do together. is inquiry could

be expanded to include geographically focused support-

ing questions such as: Where does my family live? How do

location and place aect what families do together? Where

does my family come from? Why do some families travel

to other places? e lesson presented in this article can be

used to teach foundational map reading skills that can help

K–2 students contextualize information related to the topic

of families, as well as other social studies topics.

Explicit Instruction

Explicit instruction is an evidence-based approach to teach-

ing characterized by a sequence of intentionally designed

supports with practice and feedback that guides students

through the learning process.

12

Research has shown that

explicit instruction can be applied in many grade levels

and subjects, and the method is particularly benecial for

students with disabilities.

13

Archer and Hughes oer a list of six teaching practices

for explicit instruction that includes review, presentation

of the lesson, guided practice, corrections and feedback,

independent practice, and weekly and monthly reviews.

14

Another approach is Fisher and Frey’s I do, we do, you do

structured teaching framework (see Table 1), which aligns

to principles of explicit instruction: teachers should state a

clear purpose for learning and model skills/techniques, oer

teacher-assisted (guided) practice with feedback, and gradu-

ally engage students in independent practice. Collaborative

practice (i.e., “you do it together”), where students practice

with each other, is an additional pedagogical tool in this

framework.

15

As the activities in this article demonstrate,

the I do, we do, you do approach can easily be applied to

map skills instruction.

Using the I Do, We Do, You Do Framework with

Maps

An eective way to plan a lesson with the I do, we do, you do

approach is to start by stating a clear, standards-based learning

objective. Beginning with the outcome in mind—what you

want students to be able to know and do—can help teachers

decide how to break the task into small sequential steps.

is section oers an explicit lesson used with rst graders

for the following learning objective: e students will use

cardinal directions to locate states on a United States political

map. e rst graders who participated in this lesson were

introduced to a compass rose during a prior lesson. Although

this lesson used student desk maps and a classroom smart

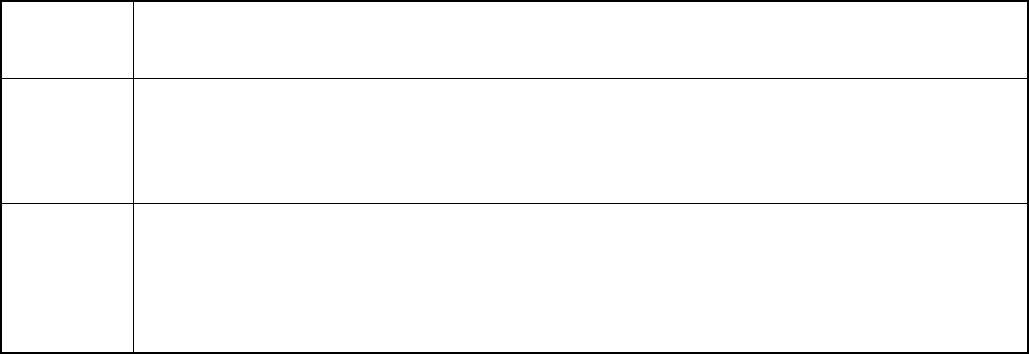

Table . Summary of Explicit Instruction Components in the I Do, We Do, You Do Model

Structured Teaching

Framework Stages

1

Elements of Explicit Instruction

2

Explain

Review prior knowledge.

Provide a clear description of the lesson outcomes and why the lesson is relevant for students.

I Do

Break the task down into small steps.

Demonstrate the task while talking students through each step using clear, direct language.

Use examples and non-examples.

We Do

Guide students to practice the task along with you until they can complete the task with few or no errors.

Offer correction and reteaching as needed using clues, prompting, and specific feedback; Gradually remove

supports as students are successful.

You Do

Provide affirmative or corrective feedback as needed during initial independent practice.

Allow students to practice the task until they demonstrate fluency, or repeated success.

1. Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey, Better Learning through Structured Teaching: A Framework for the Gradual Release of Responsibility, 3rd ed. (Alexandria, VA:

Association of Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2021).

2. Anita L. Archer and Charles A. Hughes, Explicit Instruction: Eective and Ecient Teaching (New York: Guilford Press, 2011).

30 Social Studies and the Young Learner

board, printed copies of simple U.S. political maps, atlases,

or other maps may be used.

Explain

e rst stage of an explicit lesson is to review what students

already know, explain what they will learn during this lesson,

and describe why the lesson is important. For the rst-grade

lesson objective to use cardinal directions, the student teacher

began by saying,

Let’s look back at the compass rose we made during

our previous lesson, which shows the four cardinal

directions and how to arrange them in relation to

each other. [Show a compass rose.]

I will name each cardinal direction as I point to it

on the compass rose. Watch me and listen as I read:

north, east, south, west.

Earlier, we learned a trick to remember the cardi-

nal directions in order by saying, “Never eat soggy

waes”: Never (north), Eat (east), Soggy (south),

Waes (west).

Together, let’s repeat the names of the cardinal

directions in order: north, east, south, west.

Today, you will learn how to use the four cardinal

directions on a map of the United States to nd

several states in our country.

Knowing how to use directions on a map can help

you gure out how to get to or nd another place.

Knowing how to use directions on a map of the

United States can help you learn about where you

live and where people in other states live.

I Do

During the I do phase, the teacher demonstrates how to do

the skill in a series of clear steps while describing each step

aloud. Importantly, several examples should be provided

in this way alongside non-examples or incorrect outcomes.

Begin with very easy examples and, if needed, model more

challenging examples. e student teacher’s lesson continued:

First, let’s look at this simple map of the United

States on our class smart board. You will be given

a map just like this one in a few minutes.

I will tape four note cards around the outside edges

of the map to label the four cardinal directions in

the same order in which we learned them.

Watch me place the north card here just above the

map, the east card on the right side of the map, the

south card underneath the map, and the west card

on the le side of the map. Placing the cardinal

direction cards around the map will help me learn

to use those directions to locate places on the map.

Next, watch how I can use our direction cards to

help me travel from one state to another state.

Here is Kansas—I will point to it. Some of you have

visited the state of Kansas before. Watch me trace

my nger around the border of Kansas.

Let’s imagine I have my car in Kansas, and I want

to visit a friend who is in a state that is just to

the north of Kansas. I will nd the direction card

labeled north [point to it] and move my nger

from Kansas toward the top of the map, toward the

north. e rst state that I nd north of Kansas is

Nebraska. Watch me use my nger again to trace a

line that starts in Kansas and goes north. Nebraska

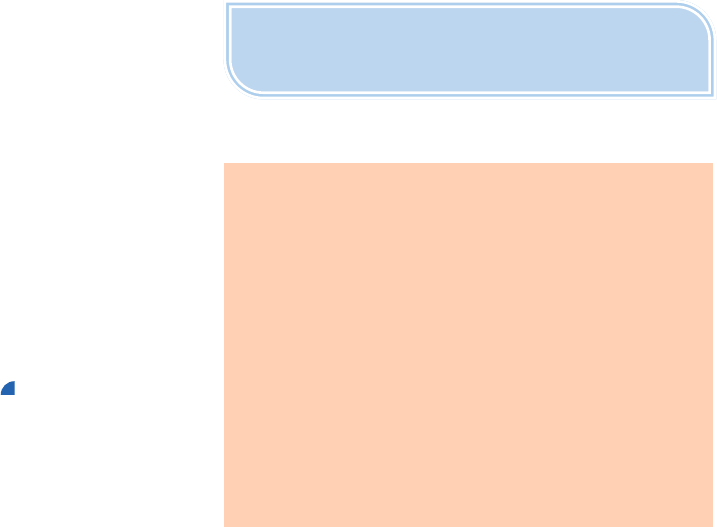

Table . Texas Standards Connected to Map Skills*

Kindergarten

The student is expected to:

(3C) identify and use geographic tools…including maps and globes.

(14D) create and interpret visuals, including pictures and maps.

Grade 1

The student is expected to:

(3B) locate places using the four cardinal directions.

(4) create and use simple maps of the home, classroom, school, and community; and locate and explore the

community, Texas, and the United States on maps and globes.

(17D) create and interpret visual and written material.

Grade 2

The student is expected to:

(3A) identify and use information on maps and globes using basic map elements such as title, cardinal directions,

and legend.

(4B) locate places…on maps and globes.

(15A) gather information about a topic using a variety of…sources such as…maps.

(16F) create written and visual materials such as…maps…to express ideas.

*Texas Admin. Code § 113.11–13 (2018).

November/December 2023 31

is north of Kansas.

Next, let’s imagine that I have another friend located

in the state that is just to the east of Kansas. Watch

me nd the direction card labeled east on the map

so I will know which direction to move my nger.

I will start with my nger in Kansas and move it in

a straight line toward the east. e rst state that

I come to is Missouri. Missouri is east of Kansas.

e student teacher continued modeling how to nd

adjacent states to the south and west of Kansas. is same

process can be used with any state that is surrounded by

other states that are easy to locate with cardinal directions.

Once Colorado was identied as a state located to the west

of Kansas, the student teacher modeled a more challenging

imaginary road trip by traveling two states to the west of

Kansas, landing in Utah. Continuing with this example, the

children were shown that the farther in one direction they

traveled, the more states they passed through.

As a non-example, the student teacher traced their nger

in the wrong direction, heading east when the goal was to

travel west. Talking the children through the process of

problem-solving by orienting them to the direction cards

around the map can help them with accuracy.

At this stage and during guided practice, the student

teacher anticipated students’ questions about states located

with intermediate directions (e.g., northeast, southwest).

e student teacher knew that a simple explanation about

intermediate directions could be provided, perhaps with a

statement that they would be learning more about those

during another lesson.

We Do

We do involves rehearsing with students to give them

opportunities to practice the skill that was modeled during

the I do phase. e goal in this phase is to oer enough

practice, correction, and feedback so students experience

success with assistance and gain condence with the

skill. As practice continues, teacher assistance is gradually

withdrawn. For this lesson, this phase involved the student

teacher saying,

Let’s practice using cardinal directions to locate

some other states. You will use your own desk maps

to practice with me.

First, let’s work together to label the cardinal direc-

tions around the edges of your desk maps.

Next, let’s point to each cardinal direction on our

maps and say the words together, in the order we

learned them: north, east, south, west.

I have already shown you how I used cardinal

directions to nd states near Kansas.

is time, let’s start in the state of Texas. [Point to

Texas on your map and wait for students to nd it

on their desk maps.] Imagine that I wanted to travel

to a state that is east of Texas. I can see where east is

labeled on my map, here on the right side. Put your

nger in Texas and trace a straight line toward the

east while I do the same on our smart board. We

are in Louisiana! Louisiana is east of Texas.

Next, let’s see if we can nd a state that is north

of Texas. Use a nger to trace a straight line from

Texas toward the north. What is the rst state we

nd that is north of Texas? How many other states

are north of Texas? Let’s count them together…

You Do

is phase involves continued practice with a partner or

individually. Students should be given enough opportunities

to practice so they experience repeated success with the skill

on their own. During the You do phase, the teacher should

oer positive feedback and check for understanding as

needed. For example, the teacher could say, “You correctly

found two states that are to the west of Tennessee. How did

you gure that out?”

Corrective feedback should include specic guidance.

For example,

You are so close to nding a state that is to the west

of Tennessee. Let’s review where the west is on our

map. Can you point to the label that says west? Put

your nger on Tennessee and trace a line toward

the west. Stop when you see a state that is west of

Tennessee. Point to that state’s name. Arkansas—

correct!

e You do phase allows teachers to determine whether

students met the lesson objective. e rst graders who

were guided through the I do, we do, you do process to learn

how to use cardinal directions to nd states on a U.S. map

were given a list of questions to answer on their own using

cardinal directions. e questions were very similar to the

prompts used during the I do and We do phases of the lesson;

the student teacher had intentionally set the rst graders

up for success by having ample opportunities to practice

with guidance. By the end of the lesson, these rst graders

could correctly identify states to the north, east, and west

of a given state along the Gulf Coast. e assessment also

gave students opportunities to identify states they had vis-

ited or knew about, which made the assignment personally

meaningful. One rst grader proudly announced that her

grandmother lives two states north of her home state, dem-

onstrating accurate use of cardinal directions and interest

in her personal connection to the lesson.

32 Social Studies and the Young Learner

Additional Recommendations for Teaching

Map Skills

Some teachers believe there is not enough time during the

school day to teach geographic skills. However, lessons that

teach children to use/create maps do not need to take a lot

of class time. Depending on students’ prior knowledge and

the complexity of the standard you are teaching, many map

lessons can be completed in 15–20 minutes. (See Table 2 for

K–2 standards related to map skills in Texas.) Furthermore,

not all map activities require the full I do, we do, you do pro-

cess. For example, teachers can use Google Earth, classroom

wall maps, and other kinds of maps to show students the

relative and absolute locations of places they are exposed

to during reading, science, history, and discussions about

current events. Similarly, review and guided practice with

map concepts can be oered throughout the day. Examples

are puzzles requiring spatial thinking, construction activities

with blocks, position word games such as I Spy or Simon

Says, and read alouds that refer to specic geographic regions

or locations.

One way to make the most of the time you have to teach

about maps and with maps is to cultivate students’ curios-

ity about maps. Developmentally appropriate maps that are

simple to interpret will naturally spark children’s interest,

especially when the maps show familiar or interesting places

such as their own classroom, community, state, or a nearby

playground, park, or zoo. Like the rst graders described

in the opening vignette who eagerly identied their own

state before their map lesson began, it is recommended that

students have opportunities explore a new map on their

own for a few moments before instruction begins. Even if

students cannot yet interpret the legend or read the words,

allowing them to investigate maps prior to instruction can

help students settle into the lesson once their initial excite-

ment has been expressed. See the sidebar on this page for a

list of websites that contain free resources for teaching map

skills to students in early grades.

Conclusion

e explicit I do, we do, you do instructional framework is a

valuable instructional approach for teaching early map skills

to young children.

By providing young students with carefully

planned, sequential map exercises that they observe, practice

using (with support), then execute independently, teachers

can promote geographic understanding while cultivating

broader skills in spatial thinking. ese skills, in turn, will

enrich children’s understanding of geographic themes to help

them contextualize what they are learning in other social

studies disciplines and core subjects.

Notes

1. Student teachers were enrolled in the author’s social studies methods course

where the I Do, We Do, You Do process was introduced along with the

activities described in the sample lesson. e student teachers then co-

wrote explicit geography lesson plans, revised them aer receiving feedback,

and taught the lessons to students at the university’s laboratory school for

children with mild learning disabilities.

2. David Sobel, Mapmaking with Children: Sense of Place Education for the

Elementary Years (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 1998).

3. National Research Council (NRC), Learning to ink Spatially

(Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2006), ix.

4. Sarah Witham Bednarz, “Geography’s Secret Powers to Save the World,”

e Canadian Geographer 63, no. 4 (2019): 520–529.

5. NRC, Learning to ink Spatially.

6. Eugene Geist, “Let’s Make a Map: e Developmental Stages of Children’s

Mapmaking,” YC Young Children 71, no. 2 (2016): 50–55; Philip J. Gersmehl

and Carol A. Gersmehl, “Spatial inking by Young Children: Neurologic

Evidence for Early Development and ‘Educability,’” Journal of Geography

106, no. 5 (2007): 181–191; NRC, Learning to ink Spatially.

7. National Council for the Social Studies, e College, Career, and Civic Life

(C3) Framework for Social Studies State Standards: Guidance for Enhancing

the Rigor of K-12 Civics, Economics, Geography, and History (Silver Spring,

MD: National Council for the Social Studies, 2013), 40.

8. Bednarz, “Geography’s Secret Powers to Save the World,” 522.

9. Susan Heron and Roger Downs, eds., Geography for Life: e National

Geography Standards, 2nd ed. (Silver Spring, MD: National Council for

Geographic Education, 2012), https://ncge.org/teacher-resources/national-

geography-standards/.

10. Sarah Witham Bednarz, Gillian Acheson, and Robert S. Bednarz, “Maps

and Map Learning in Social Studies,” Social Education 70, no. 7 (2006):

398–432; Noreen Naseem Rodríguez and Katy Swalwell, Social Studies for

a Better World: An Anti-Oppressive Approach for Elementary Educators

(New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2021).

11. C3 Teachers, “Family,” https://c3teachers.org/inquiries/family/.

12. Anita L. Archer and Charles A. Hughes, Explicit Instruction: Eective and

Ecient Teaching (New York: Guilford Press, 2011).

13. e.g., Roy Corden, “Developing Reading-Writing Connections: e Impact

of Explicit Instruction of Literary Devices on the Quality of Children’s

Narrative Writing,” Journal of Research in Childhood Education 21, no. 3

(2007): 269–289; Vanessa Hinton, Shaunita Stroizer, and Margaret Flores,

“A Case Study in Using Explicit Instruction to Teach Young Children

Counting Skills,” Investigations in Mathematics Learning 8, no. 2 (2015):

37–54.

14. Archer and Hughes, Explicit Instruction.

15. Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey, Better Learning through Structured

Teaching: A Framework for the Gradual Release of Responsibility, 3rd ed.

(Alexandria, VA: Association of Supervision and Curriculum Development,

2021).

Michelle Bauml is a Professor of Early Childhood/Social Studies Edu-

cation at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth, Texas. She can be

reached at

.

Free Resources for Teachers

C3 Teachers, www.c3teachers.org

Enter “geography” in the topic search bar for several K–5

inquiries about maps, globes, and geography.

National Council for Geographic Education, https://ncge.org/

Access numerous free and members-only resources for

teaching geography.

National Geographic, http://education.nationalgeographic.org

This resource library includes maps, videos, articles, and other

resources for teaching geography